Several years ago, a friend of mine took a trip to Italy. This was before I first went to Italy myself. When she came back she brought me a souvenir. It was a small statue of Michelangelo's David. She said that she wanted to bring me back the perfect man. She thought there was no better gift for me, and I have to agree. David is perfection in beauty.

Several years ago, a friend of mine took a trip to Italy. This was before I first went to Italy myself. When she came back she brought me a souvenir. It was a small statue of Michelangelo's David. She said that she wanted to bring me back the perfect man. She thought there was no better gift for me, and I have to agree. David is perfection in beauty.

So for today’s post I wanted to feature two of my favorite Renaissance artists. Both of whom are believed to have been gay. The first is Michelangelo (the other is Michelangelo also, but a different one).

Michelangelo was born March 6, 1475, in Caprese, Republic of Florence and died Feb. 18, 1564, in Rome, Papal States. He was an Italian sculptor, painter, architect, and poet. He served a brief apprenticeship with Domenico Ghirlandaio in Florence before beginning the first of several sculptures for Lorenzo de'Medici. After Lorenzo's death in 1492, he left for Bologna and then for Rome. There his Bacchus (1496 – 97) established his fame and led to a commission for the Pietà (now in St. Peter's Basilica), the masterpiece of his early years, in which he demonstrated his unique ability to extract two distinct figures from one marble block. His David (1501 – 04), commissioned for the cathedral of Florence, is still considered the prime example of the Renaissance ideal of perfect humanity. On the side, he produced several Madonnas for private patrons and his only universally accepted easel painting, The Holy Family (known as

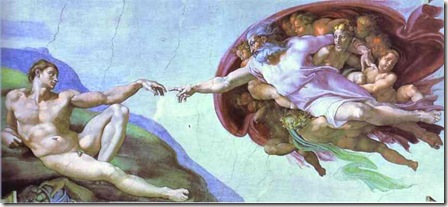

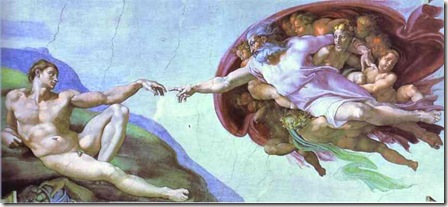

Michelangelo was born March 6, 1475, in Caprese, Republic of Florence and died Feb. 18, 1564, in Rome, Papal States. He was an Italian sculptor, painter, architect, and poet. He served a brief apprenticeship with Domenico Ghirlandaio in Florence before beginning the first of several sculptures for Lorenzo de'Medici. After Lorenzo's death in 1492, he left for Bologna and then for Rome. There his Bacchus (1496 – 97) established his fame and led to a commission for the Pietà (now in St. Peter's Basilica), the masterpiece of his early years, in which he demonstrated his unique ability to extract two distinct figures from one marble block. His David (1501 – 04), commissioned for the cathedral of Florence, is still considered the prime example of the Renaissance ideal of perfect humanity. On the side, he produced several Madonnas for private patrons and his only universally accepted easel painting, The Holy Family (known as  the Doni Tondo). Attracted to ambitious sculptural projects, which he did not always complete, he reluctantly agreed to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel (1508 – 12). The first scenes, depicting the story of Noah, are relatively stable and on a small scale, but his confidence grew as he proceeded, and the later scenes evince boldness and complexity. His figures for the tombs in Florence's Medici Chapel (1519 – 33), which he designed, are among his most accomplished creations. He devoted his last 30 years largely to the Last Judgment fresco in the Sistine Chapel, to writing poetry (he left more than 300 sonnets and madrigals), and to architecture. He was commissioned to complete St. Peter's Basilica, begun in 1506 and little advanced since 1514. Though it was not quite finished at Michelangelo's death, its exterior owes more to him than to any other architect. He is regarded today as among the most exalted of artists.

the Doni Tondo). Attracted to ambitious sculptural projects, which he did not always complete, he reluctantly agreed to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel (1508 – 12). The first scenes, depicting the story of Noah, are relatively stable and on a small scale, but his confidence grew as he proceeded, and the later scenes evince boldness and complexity. His figures for the tombs in Florence's Medici Chapel (1519 – 33), which he designed, are among his most accomplished creations. He devoted his last 30 years largely to the Last Judgment fresco in the Sistine Chapel, to writing poetry (he left more than 300 sonnets and madrigals), and to architecture. He was commissioned to complete St. Peter's Basilica, begun in 1506 and little advanced since 1514. Though it was not quite finished at Michelangelo's death, its exterior owes more to him than to any other architect. He is regarded today as among the most exalted of artists.

Fundamental to Michelangelo's art is his love of male beauty, which attracted him both aesthetically and emotionally. In part, this was an expression of the Renaissance idealization of masculinity. But in Michelangelo's art there is clearly a sensual response to this aesthetic.

Fundamental to Michelangelo's art is his love of male beauty, which attracted him both aesthetically and emotionally. In part, this was an expression of the Renaissance idealization of masculinity. But in Michelangelo's art there is clearly a sensual response to this aesthetic.

The sculptor's expressions of love have been characterized as  both Neoplatonic and openly homoerotic; recent scholarship seeks an interpretation which respects both readings, yet is wary of drawing absolute conclusions. One example of the conundrum is Cecchino dei Bracci, whose death, only a year after their meeting in 1543, inspired the writing of forty eight funeral epigrams, which by some accounts allude to a relationship that was not only romantic but physical as well:

both Neoplatonic and openly homoerotic; recent scholarship seeks an interpretation which respects both readings, yet is wary of drawing absolute conclusions. One example of the conundrum is Cecchino dei Bracci, whose death, only a year after their meeting in 1543, inspired the writing of forty eight funeral epigrams, which by some accounts allude to a relationship that was not only romantic but physical as well:

La carne terra, e qui l'ossa mia, prive

de' lor begli occhi, e del leggiadro aspetto

fan fede a quel ch'i' fu grazia nel letto,

che abbracciava, e' n che l'anima vive.

The flesh now earth, and here my bones,

Bereft of handsome eyes, and jaunty air,

Still loyal are to him I joyed in bed,

Whom I embraced, in whom my soul now lives.

The greatest written expression of his love was given to Tommaso dei Cavalieri (c. 1509–1587), who was 23 years old when Michelangelo met him in 1532, at the age of 57. Cavalieri was open to the older man's affection: I swear to return your love. Never have I loved a man more than I love you, never have I wished for a friendship more than I wish for yours. Cavalieri remained devoted to Michelangelo until his death.

The greatest written expression of his love was given to Tommaso dei Cavalieri (c. 1509–1587), who was 23 years old when Michelangelo met him in 1532, at the age of 57. Cavalieri was open to the older man's affection: I swear to return your love. Never have I loved a man more than I love you, never have I wished for a friendship more than I wish for yours. Cavalieri remained devoted to Michelangelo until his death.

The sonnets are the first large sequence of poems in any modern tongue addressed by one man to another, predating Shakespeare's sonnets to his young friend by fifty years.

I feel as lit by fire a cold countenance

That burns me from afar and keeps itself ice-chill;

A strength I feel two shapely arms to fill

Which without motion moves every balance.

(Michael Sullivan, translation)

As great as he was, Michelangelo always depicted the penis too small both in sculpture and frescoes. And of course he exaggerated David's hands to show their strength and agility in killing Goliath. Perhaps, since so many of his works were commissioned Biblical works, he felt that he had to make them concur with whatever was the current thinking of the time.

ReplyDeleteWhere do you get all the lovely young men depicting art scenes, such as Rodin's Thinker and Michelangelo's Creation? I would love to have a book with the original art on the left page and the young man imitating it on the facing page!

Uncutplus, Michelangelo often depicted penises as small because he had to keep his commissions with the church. Do you remember when Jamaica did their sculpture at Emancipation park in commemoration of the slaves who worked on the island? People were upset because the penis was so large (I plan to do a post on it in the future). It would have been much worse for Michelangelo.

ReplyDeleteAs for where I find the pictures of the men and art in my blog, I generally do a Google image search for pictures that I don't already have, and sometimes I am pleasantly surprised at what pops up.

How did the church hire so many obviously gay artists when they were/are anti-gay?

ReplyDeleteI don't think the church had a choice in the matter. They wanted the best, and during the Renaissance, especially in Florence where homosexuality was legal, the great artists of the Florentine Renaissance were often gay. The church just wanted to make sure two things: that the artists didn't flaunt their sexuality and that they produced the best work.

ReplyDeleteThis is also a time period when the Catholic Church was not on the moral high ground. Popes, bishops, and priests were having sexual relations, even though they were supposed to be celibate. They were buying church offices, selling the pathway to heaven (indulgences), and many, many other abuses. It was far more important during this time to have the most beautiful art and cathedrals than it was to police morality.