The first-person narrative centers around David, a white American attempting to “find himself” in France. The novel opens in the present with David recalling his internecine upbringing and an adolescent homosexual encounter. In Paris awaiting the return of his girlfriend and possible fiancée, Hella, David engages in a torrid affair with Giovanni, an Italian bartender. Giovanni loves him unashamedly, and they live together for two months; however, David transforms Giovanni's room into a symbol of their “dirty” relationship. Upon Hella's return from Spain, David abruptly leaves the

Meanwhile, David, despondent over his mistreatment of Giovanni and the truth about his homosexuality, attempts to rejuvenate himself via marriage. But upon discovering him and a sailor in a gay bar, Hella vows to return to America, wishing “I’d never left it.” The novel's closing tableau replicates its opening: David ponders Giovanni's impending execution and his complicity in his erstwhile lover's demise.

Giovanni's Room fuses the personal, the actual, and the fictional: Baldwin exorcises demons surrounding his own sexual identity while simultaneously capturing the subterranean milieu he encountered in Paris during the late 1940s and early 1950s; he bases the murder plot on an actual crime involving the killing of an older man who purportedly propositioned a younger one; and he weaves a Jamesian tale of expatriate Americans fleeing their “complex fate” in search of their “true” selves. The novel received favorable reviews, many critics applauding

Giovanni's Room was the first gay novel I ever read. I found it utterly fascinating and it began my life long pursuit and love of gay novels. It is not a happy novel, but it is well worth reading. Baldwin became and inspiration to me. Recently while listening to NPR, Morning Edition did a story about a a new collection of his works edited by Randall Kenan called The Cross of Redemption. Here is an excerpt from the transcripts of this story:

The writer James Baldwin once made a scathing comment about his fellow Americans: "It is astonishing that in a country so devoted to the individual, so many people should be afraid to speak."

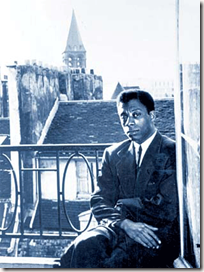

As an openly gay, African-American writer living through the battle for civil rights, Baldwin had reason to be afraid — and yet, he wasn't. A television interviewer once asked Baldwin to describe the challenges he faced starting his career as "a black, impoverished homosexual," to which Baldwin laughed and replied: "I thought I'd hit the jackpot."

I wish that all of the GLBT population in the world could feel each day like they’d “hit the jackpot."

baldwin has also become an inspiration to me - thanks for this post as I didn't know of his new book... his work speaks eternally of a wounded body, and soul, but also of a resilience, a beautiful passion...

ReplyDeleteThe new book does sound interesting. He is such a great writer. I know he was not technically part of the Harlem Renaissance, but I couldn't leave him out.

ReplyDelete