|

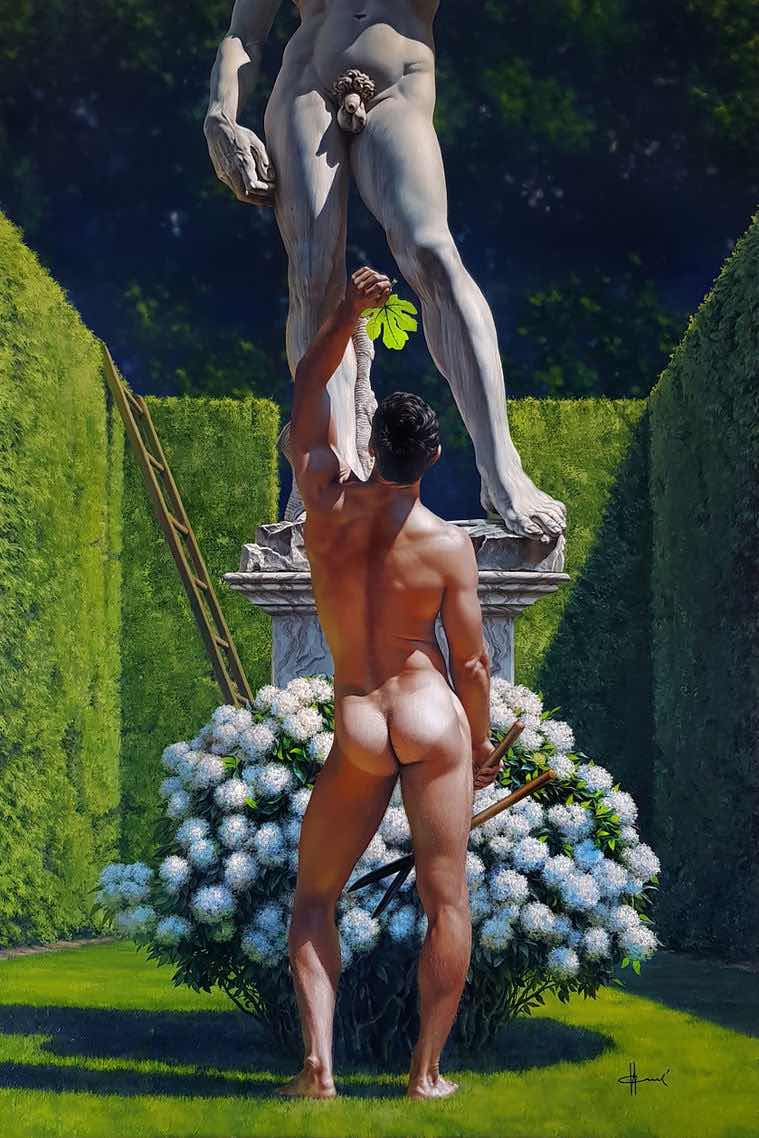

| Leaf of Sanctimony by Igor Sychev |

The Renaissance was a period of extraordinary artistic innovation, deeply rooted in the revival of classical antiquity. One of the most striking aspects of this artistic rebirth was the depiction of the male nude, which emerged as a central subject in painting and sculpture. Inspired by the idealized human form of ancient Greek and Roman art, Renaissance artists sought to depict the male body with a renewed emphasis on anatomical precision, movement, and harmony. Through their works, they celebrated the human body not only as a physical entity but as a symbol of intellectual and moral excellence.

The Renaissance aesthetic for the male nude was heavily influenced by the rediscovery of Greco-Roman sculptures, such as the

Doryphoros of Polykleitos and the

Laocoön and His Sons. These works provided artists with a model for idealized proportions, muscularity, and contrapposto—a stance in which the body's weight is shifted onto one leg, creating a dynamic yet balanced composition. Renaissance humanism further reinforced this fascination with the body, as artists and scholars viewed the human form as a reflection of divine beauty and the perfection of nature.

|

Donatello’s David (c. 1440-1460) |

One of the earliest and most significant Renaissance depictions of the male nude is Donatello’s David, a bronze sculpture that stands as a departure from medieval artistic conventions. Unlike earlier depictions of David, which were typically clothed and rigid, Donatello’s David is an entirely nude, youthful figure standing in a relaxed contrapposto stance. His slender yet graceful form recalls ancient Greek statuary, while the sensuality of his pose and delicate features introduce a new level of naturalism. This was one of the first freestanding male nudes since antiquity, marking a return to the classical ideal of the human body as a subject worthy of artistic exploration.

|

Michelangelo’s David (1501-1504) |

If Donatello’s David embodied grace and youthful beauty, Michelangelo’s David elevated the male nude to an expression of power and intellect. Created from a single block of marble, this towering figure stands over 17 feet tall, emphasizing strength and heroic idealism. Michelangelo’s meticulous study of anatomy is evident in David’s muscular definition, veins, and tense posture, reflecting both physical perfection and psychological depth. The influence of classical antiquity is clear, yet Michelangelo imbues his David with a distinctly Renaissance sense of individualism and self-awareness. Unlike Donatello’s contemplative David, Michelangelo’s version captures the moment before action, his furrowed brow and focused gaze conveying the tension of impending battle.

|

Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man (c. 1490) |

Though not a finished artwork, Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man remains one of the most iconic representations of the Renaissance fascination with the male nude. Based on the writings of the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius, Leonardo’s drawing explores the mathematical proportions of the human body, inscribing a nude male figure within both a square and a circle. This image is not only an anatomical study but a philosophical statement on the harmony between man and the universe. Leonardo, like many Renaissance artists, saw the male body as a manifestation of divine order, bridging art, science, and humanism.

|

Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam (1511-1512) |

Another of Michelangelo’s masterful depictions of the male nude is found in The Creation of Adam, a fresco on the Sistine Chapel ceiling. Here, the muscular, reclining figure of Adam reaches out toward God in a moment of divine animation. Adam’s body, sculpted with the precision of an ancient Greek athlete, exudes both physical perfection and vulnerability, symbolizing humanity’s potential and dependence on divine grace. The composition and exaggerated gestures heighten the drama of the scene, making it one of the most celebrated images of the Renaissance.

|

Raphael’s The School of Athens (1509-1511) |

While Raphael is best known for his refined, idealized figures, The School of Athens includes several striking male nudes that showcase his mastery of anatomy and composition. The figures reclining in the foreground, likely inspired by classical sculptures, demonstrate the Renaissance artist’s ability to capture the beauty of the human form while integrating it into a grand intellectual scene. Unlike Michelangelo’s muscular intensity, Raphael’s figures possess a softer elegance, reflecting the harmonious balance that defined his artistic style.

The Renaissance aesthetic for the male nude in art was a testament to the period’s renewed admiration for classical ideals, humanism, and scientific inquiry. Whether through the sensual grace of Donatello’s David, the heroic grandeur of Michelangelo’s sculptures, or the intellectual rigor of Leonardo’s anatomical studies, Renaissance artists transformed the male nude into an enduring symbol of beauty, strength, and the limitless potential of mankind. Their works not only revived ancient artistic traditions but also laid the foundation for future generations of artists who would continue to explore and celebrate the human form.

Excellent summary , as usual, for Italy , and France?

ReplyDeleteNext week: The male nude in the Gothic era ? This is Adam from Notre Dame de Paris https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adam_%28mus%C3%A9e_de_Cluny%29

Thanks for the lesson!!! I learned a lot!

ReplyDeleteI appreciate the overview, inspiring.

ReplyDeleteThe David was carved in a bloc of marble that was just the size to fit it and in a not so perfect marble which was a chalenge for him.

ReplyDeleteIt represents the young state-city of Florencia victory over its ennemies.

The body is one of a muscular young adult but to make it look younger, the hands were a bit over sized as some of teenagers.

Also for the head, he also a bit oversized it as to go against the perspecive effect of that 17 feet tall statu.

Those who say that it's so natural it shows how you have to see how an artist plays with proportions to suit the goal of it.

Many other artist did so like the «Odalisque» of Ingres where he added 3 vertebras to this lady to suit its semi arch of her back and make it more in phase with the composition.

Il est possible que la tête soit surdimensionnée car le David , à l'origine , devait être placé en hauteur sur le Duomo , mais difficile . C'est Michel-Ange qui a demandé qu'il soit placé devant le Palazzo Vecchio . Il y a eu de nombreuses copies : deux à Florence et une à Marseille aussi en marbre .

DeleteOH LA LA JiEL

DeleteÁngel

Me encanta como impartes tu pedagogía del arte José. Tus alumnos tienen mucha suerte

ReplyDeleteÁngel

Are you able to share these insights with the students in your classes?

ReplyDeleteSometimes if it’s relevant to what I’m teaching I’ll work it into my lecture.

Delete