"Hip flasks of hooch, jazz, speakeasies, bobbed hair, 'the lost generation.' The Twenties are endlessly fascinating. It was the first truly modern decade and, for better or worse, it created the model for society that all the world follows today." (from Kevin Rayburn, "Two Views of the 1920s.")

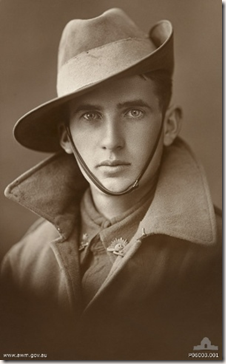

So what, beside the thought of hot soldiers in uniform, does the Veteran’s Day have to do with a gay blog? First of all, as a result of the war, came the Jazz Age, and with the Jazz Age came the Flapper. "Flapper" in the 1920s was a term applied to a "new breed" of young Western women who wore short skirts, bobbed their hair, listened to jazz, and flaunted their disdain for what was then considered acceptable behavior. Flappers were seen as brash for wearing excessive makeup, drinking, treating sex in a casual manner, smoking, driving automobiles and otherwise flouting social and sexual norms.

When the Great War was over, the survivors went home and the world tried to return to normalcy. Unfortunately, settling down in peacetime proved more difficult than expected. During the war, the boys had fought against both the enemy and death in far away lands; the girls had bought into the patriotic fervor and aggressively entered the workforce. During the war, both the boys and the girls of this generation had broken out of society's structure; they found it very difficult to return.

They found themselves expected to settle down into the humdrum routine of American life as if nothing had happened, to accept the moral dicta of elders who seemed to them still to be living in a Pollyanna land of rosy ideals which the war had killed for them. They couldn't do it, and they very disrespectfully said so (Frederick Lewis Allen, Only Yesterday: An Informal History of the Nineteen-Twenties (New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1931).

The term "flapper" first appeared in Great Britain after World War I. It was there used to describe young girls, still somewhat awkward in movement who had not yet entered womanhood. In the June 1922 edition of the Atlantic Monthly, G. Stanley Hall described looking in a dictionary to discover what the evasive term "flapper" meant:

[T]he dictionary set me right by defining the word as a fledgling, yet in the nest, and vainly attempting to fly while its wings have only pinfeathers; and I recognized that the genius of 'slanguage' had made the squab the symbol of budding girlhood.

Authors such as F. Scott Fitzgerald and artists such as John Held Jr. first used the term to the U.S., half reflecting and half creating the image and style of the flapper. Fitzgerald described the ideal flapper as "lovely, expensive, and about nineteen."

The Flappers' image consisted of drastic - to some, shocking - changes in women's clothing and hair. Nearly every article of clothing was trimmed down and lightened in order to make movement easier.

It is said that girls "parked" their corsets when they were to go dancing. The new, energetic dances of the Jazz Age, required women to be able to move freely, something the "ironsides" didn't allow. Replacing the pantaloons and corsets were underwear called "step-ins."

Too bad more gay men could not legally be out and proud during the Roaring Twenties, we can look a lot more like hot young men than a bunch of flat-chested women who called themselves Flappers.

No comments:

Post a Comment