A blog about LGBTQ+ History, Art, Literature, Politics, Culture, and Whatever Else Comes to Mind. The Closet Professor is a fun (sometimes tongue-in-cheek, sometimes very serious) approach to LGBTQ+ Culture.

Friday, June 28, 2024

TGIF!!!

Wednesday, June 28, 2023

The Stonewall Riots

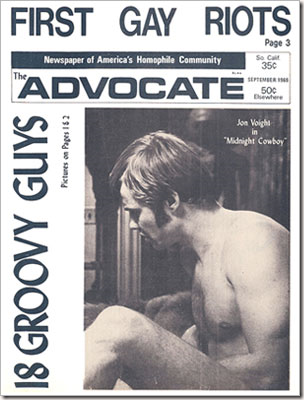

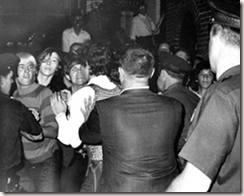

At 1:20 a.m. on Saturday, June 28, 1969, four plainclothes policemen in dark suits, two patrol officers in uniform, Detective Charles Smythe, and Deputy Inspector Seymour Pine, arrived at the Stonewall Inn's double doors and announced, "Police! We're taking the place!" The music was turned off, and the main lights were turned on. Raids of gay bars in New York City, particularly Greenwich Village, were not uncommon in the summer of 1969; what made the raid on the Stonewall on the night of June 27 so different was that the patrons of the bar resisted instead of going peacefully. Approximately 205 people were in the bar that night. Patrons who had never experienced a police raid were confused. A few who realized what was happening began to run for doors and windows in the bathrooms, but police barred the doors. The police had a standard procedure for these raids. They lined up the patrons and began checking identification. Any person appearing to be physically male and dressed as a woman would be arrested. This particular raid did not go as planned. Those dressed as women that night refused to go with the officers. Men in line began to refuse to produce their identification.

The New York Post was the first of the New York newspapers to report the raid and the first “melee” that followed the raid. The Post described the scene following the raid on the Stonewall Inn, “a tavern frequented by homosexuals at 53 Christopher St.” The raid was staged because of the unlicensed sale of liquor. On that first night, twelve people were arrested with charges ranging from assault to disorderly conduct because of the impromptu riot that soon ensued. As the police drove away with those in custody from the raid, the newspaper describes how “hundreds of passerby” shouted “Gay Power” and “We Want Freedom” while laying siege to the bar with “an improvised battering ram, garbage cans, bottles and beer cans in a protest demonstration.” More police were sent to 53 Christopher Street, where the disturbance raged for more than two hours.

For the next two days and again on July 3, the New York Times ran small pieces about the “Village Raid.” On June 29, the Times reported that shortly after 3 a.m. on the previous day, the bar had been raided. About two hundred patrons were thrown out of the bar and soon were joined by about two hundred more in protest of the raid. Police seized several cases of liquor from the establishment, which the police stated was operating without a liquor license. The Times reported that the “melee” lasted for only about forty-five minutes after the raid before the crowd dispersed, and thirteen people in all were arrested, with four policemen suffering injuries, one a broken wrist. The June 29 article also stated that the raid was one of three conducted in the last two weeks, and on the night of June 28, “throngs of young men congregated outside the inn. . .reading aloud condemnations of the police.”

The June 30 edition of the newspaper stated that on the early morning of June 29, a crowd of about four hundred gathered again on Christopher Street, and a Tactical Patrol Unit was called in to control the disturbance at about 2:15 a.m. The crowd was throwing bottles and lighting small fires. With their arms linked, the police made sweeps down Christopher Street from the Avenue of the Americas to Seventh Avenue, but the crowds merely moved into side streets and reformed behind the police. Those who did not move out of the way of the police line were pushed along, and two men were clubbed to the ground. Stones and bottles were thrown at the police, and twice, the police broke ranks to charge the crowd. Three people were arrested on charges of harassment and disorderly conduct. The June 30 article also stated that the crowd gathered again on the evening of June 29 to denounce the police for “allegedly harassing homosexuals.” Graffiti painted on the boarded-up windows of the inn stated, “Support gay power” and “Legalize gay bars.” A July 3 article in the New York Times stated that a chanting crowd of about five hundred gathered again outside the Stonewall Inn and had to be dispersed by the police while four protestors were arrested.

On July 3, 1969, The Village Voice published two more substantial articles on the incidents surrounding the Stonewall Inn. Of the two articles, Lucian Trusctott IV’s article is written in a tongue-in-cheek style focusing on the several days of riots that ensued after the first raid. Truscott reports that the crowd, which returned on Saturday night, was being led by “gay power” cheers: “We are the Stonewall girls/ We wear our hair in curls/ We have no underwear/ We show our pubic hair!” The article is mostly sympathetic to the gay cause and quotes Allen Ginsberg, a gay activist, stating, “Gay Power! Isn’t that great! We’re one of the largest minorities in the country--10 percent, you know. It’s about time we did something to assert ourselves.” Truscott is prophetic when he ended his article by stating:

We reached Cooper Square, and as Ginsberg turned to head toward home, he waved and yelled, “Defend the fairies!” and bounce on across the square. He enjoyed the prospect of “gay power” and is probably working on a manifesto for the movement right now. Watch out. The liberation is under way!

Gay liberation was underway.

No one really knows what set off the “flash of anger” that began the riots. Most of the people who were there just said that all of a sudden, the crowd grew angry and either began throwing bottles or trying to free one of the men in drag who were being arrested. Even if it cannot be determined what set off the anger that went through the crowd, it must be asked why that night. Many factors could have contributed to why the people in the Stonewall Inn fought back. It could have been because most of them had reached their breaking point, with the criminalization of their behavior to the Vietnam War that had raged for the last four years in the living rooms of every American with a television. One theory is that with Judy Garland’s funeral earlier that day, the men in the Stonewall Inn were distraught over losing their greatest icon. The heat in New York that summer was probably another factor. Also, the Stonewall raid occurred early in the morning. Usually, raids happened earlier in the evening so that the bar could open back up. The mafia ran the gay bars, and the police were being bribed. The raids were rarely major incidents, nor were the raids expected to be. But the night of June 27, 1969, was different for one reason or another.

Once the crowd began to fight back, the fervor of rebellion and the feeling that a revolution was happening among the gay community swept through the crowd. No longer were gays going to work with the system to make themselves feel more normal. They wanted to be accepted for who they were, not for who the establishment wanted them to be. African-Americans had made great strides in their civil rights struggle, and women were just beginning to make strides for women’s liberation and equality. As pointed out by Alan Ginsberg earlier, gays and lesbians were a large minority in the United States. If they could make themselves heard, this could change everything for them.

A catalyst had been sparked by the Stonewall Riots, and there was no turning back. From 1969 to today has been a bumpy road in the fight for LGBTQ+ rights. The AIDS epidemic set back the movement as many in the gay community died, but the fight lived on. In 1973, the board of the American Psychiatric Association voted to declassify homosexuality as a mental disorder. Eventually, the Supreme Court overturned sodomy laws and ruled in favor of gay marriage. The movement isn’t over, and we cannot rest on those and the many other small victories. With transgender rights being attacked in so many states, we have to continue to push for LGBTQ+ equality.

Saturday, June 27, 2020

The Stonewall Inn

|

| The Stonewall Inn, November 2019 |

Last November while visiting my friend Susan in Manhattan, she took me down to Greenwich Village to see the actual Stonewall Inn. It was a special moment for me. One of the best pictures of me taken in a long time was taken by Susan of me in front of Stonewall Inn. We even went inside the bar, which was not crowded in the middle of the day, and it was one of the darkest lit bars I have ever been in. It was really interesting to see and experience. Fifty-one years ago today, the Stonewall Riots began when police raided the bar. The Riot continued for the next three nights. Raids of gay bars in New York City, particularly Greenwich Village, were not uncommon in the summer of 1969. What made the raid on the Stonewall on June 27 so different was that the patrons of the bar resisted instead of going peacefully.

Today, the Stonewall inn is a national monument. Often referred to as “the birth of the modern LGBTQ rights movement,” the bar was designated a national monument to LGBTQ rights in 2016. However, the historic Stonewall Inn is on the verge of closure after the coronavirus pandemic forced it to close for the past several months. The owners have launched a crowdfunding initiative to save the bar and community landmark.

According to the GoFundMe page, the owners said, “We are reaching out because like many families and small businesses around the world, the Stonewall Inn is struggling. Our doors have been closed for over three months to ensure the health, safety, and well-being of patrons, staff and the community. Even in the best of times it can be difficult to survive as a small business and we now face an uncertain future. Even once we reopen, it will likely be under greatly restricted conditions limiting our business activities.”

The owners continued, “We resurrected the Stonewall Inn once after it had been shuttered—and we stand ready to do it again—with your help. We worked diligently to resurrect it as a safe space for the community and to keep the Stonewall Inn at the epicenter of the fight for the LGBTQ+ rights movement. It has been a community tavern, but also a vehicle to continue the fight that started there in 1969. Stonewall is the place the community gathers for celebrations, comes to grieve in times of tragedy, and rally to continue the fight for full global equality.”

“Today, we are asking you to help Save Stonewall!” they wrote. “The Stonewall Inn faces an uncertain future and we are in need of community support. The road to recovery from the COVID 19 pandemic will be long and we need to continue to safeguard this vital piece of living history for the LGBTQ community and the global human rights movement and we now must ask for your help to save one of the LGBTQ+ communities most iconic institutions and to keep that history alive.”

As I write this, the effort has raised $211,095 of their $225,000 goal. The bar also has a separate GoFundMe to help pay staff who have been unemployed during the shutdown. Also, as I was writing this, $34,383 has been raised of $60,000 goal since it was launched in April. I know times are tough right now for many people, but if you can contribute, I ask that you do. I would hate to see this historic landmark be shuttered again.

If you want to read more about the Stonewall Riots, I did a number of posts about the early gay rights movement and the Stonewall Riots on this blog about ten years ago.

Friday, June 28, 2019

Gay Rights Movement: Post Stonewall

Thursday, June 27, 2019

Gay Rights Movement: Stonewall Riots

We reached Cooper Square, and as Ginsberg turned to head toward home, he waved and yelled, “Defend the fairies!” and bounce on across the square. He enjoyed the prospect of “gay power” and is probably working on a manifesto for the movement right now. Watch out. The liberation is under way![5]

Wednesday, June 26, 2019

Gay Rights Movement: The Anti-War Movement

Tuesday, June 25, 2019

Gay Rights Movement: Mattachine Society

Friday, June 29, 2012

Stonewall Uprising

When police raided the Stonewall Inn, a popular gay bar in the Greenwich Village section of New York City on June 28, 1969, the street erupted into violent protests that lasted for the next six days. The Stonewall riots, as they came to be known, marked a major turning point in the modern gay civil rights movement in the United States and around the world.

In this 90-minute film, AMERICAN EXPERIENCE draws upon eyewitness accounts and rare archival material to bring this pivotal event to life. Based on David Carter's critically acclaimed book, Stonewall: The Riots that Sparked the Gay Revolution, Stonewall Uprising was produced by Kate Davis and David Heilbroner.

For more information about the beginnings of the Gay Rights Movement in the United States and the Stonewall Riots, please check out my series of post on Stonewall.

Tuesday, June 28, 2011

Stonewall Riots

The Stonewall riots were a series of spontaneous, violent demonstrations against a police raid that took place in the early morning hours of June 28, 1969, at the Stonewall Inn, in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of New York City. They are frequently cited as the first instance in American history when people in the homosexual community fought back against a government-sponsored system that persecuted sexual minorities, and they have become the defining event that marked the start of the gay rights movement in the United States and around the world.

Wednesday, September 22, 2010

Gay Rights Movement: Post-Stonewall

Not all gays believed that the riots and “revolution” were a good thing. The older and more wealthy gay men who frequented Fire Island in the summer either ignored the riots or were embarrassed by then. They belonged to the beliefs of the Mattachine Society who believed in assimilation and accommodationist tactics. The Mattachines wanted gays to act like heterosexuals and thus blend into the greater society.[1] The differences between the accommodationists and the liberationist will be a trend in gay politics to this day.

Not all gays believed that the riots and “revolution” were a good thing. The older and more wealthy gay men who frequented Fire Island in the summer either ignored the riots or were embarrassed by then. They belonged to the beliefs of the Mattachine Society who believed in assimilation and accommodationist tactics. The Mattachines wanted gays to act like heterosexuals and thus blend into the greater society.[1] The differences between the accommodationists and the liberationist will be a trend in gay politics to this day.  On the evening of July 4, 1969, the New York Mattachine Society called a meeting. The purpose of the gathering was to stop anymore riots and to get gays and lesbians to follow more closely their view of how the revolution should proceed, mainly for them to act like straight people and gain respect among normal society. Most of the gays in the room that night were tired of the Mattachine’s tactics. They wanted a new movement, one that challenged what normal was, one that was more militant, and one in which they did not have to change who they were. That night, the gays and lesbians at the Mattachine Society meeting formed the beginnings of the Gay Liberation Front.[2]

On the evening of July 4, 1969, the New York Mattachine Society called a meeting. The purpose of the gathering was to stop anymore riots and to get gays and lesbians to follow more closely their view of how the revolution should proceed, mainly for them to act like straight people and gain respect among normal society. Most of the gays in the room that night were tired of the Mattachine’s tactics. They wanted a new movement, one that challenged what normal was, one that was more militant, and one in which they did not have to change who they were. That night, the gays and lesbians at the Mattachine Society meeting formed the beginnings of the Gay Liberation Front.[2]  The Gay Liberation Front (GLF) never had the same organizational hierarchy that the Mattachine Society had. The GLF allowed for each chapter to move in its own direction and determine how best to achieve their overall goals in their local area. The GLF was also more visible than many people actually preferred to be, but for the GLF to succeed they had no choice but to use the “We’re here, we’re queer, get used to it” tactics.[3] The GLF had their share of splinter groups and unlikely alliances, such as with the Black Panthers.

The Gay Liberation Front (GLF) never had the same organizational hierarchy that the Mattachine Society had. The GLF allowed for each chapter to move in its own direction and determine how best to achieve their overall goals in their local area. The GLF was also more visible than many people actually preferred to be, but for the GLF to succeed they had no choice but to use the “We’re here, we’re queer, get used to it” tactics.[3] The GLF had their share of splinter groups and unlikely alliances, such as with the Black Panthers.  The gay liberation movement also moved into more proper politics in the early 1990s. The AIDS epidemic took a great deal of the steam out of the movement that had continued to build during the seventies. In the early nineties, groups like the Human Rights Council, the largest gay and lesbian political action committee, the Gay and Lesbian Task Force, and the Lambda Legal Defense Fund tackled legislative and legal issues pertaining to gay and lesbian rights. Gays and lesbians even entered the political arena with a branch of the Democratic Party, the Stonewall Democrats, and with a branch of the Republican Party, the Log Cabin Republicans. The same old issues of whether gays should assimilate into society or make society accept them for who they are and at the same time have equal rights are still apparent in the splits that exist within the gay community.[4]

The gay liberation movement also moved into more proper politics in the early 1990s. The AIDS epidemic took a great deal of the steam out of the movement that had continued to build during the seventies. In the early nineties, groups like the Human Rights Council, the largest gay and lesbian political action committee, the Gay and Lesbian Task Force, and the Lambda Legal Defense Fund tackled legislative and legal issues pertaining to gay and lesbian rights. Gays and lesbians even entered the political arena with a branch of the Democratic Party, the Stonewall Democrats, and with a branch of the Republican Party, the Log Cabin Republicans. The same old issues of whether gays should assimilate into society or make society accept them for who they are and at the same time have equal rights are still apparent in the splits that exist within the gay community.[4] [1]Ibid., 206-207.

[2]Ibid., 211-212.

[3]James T. Sears, Rebels, Rubyfruit, and Rhinestones: Queering Space in the Stonewall South, (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2001), 60, 64.

[4]Benjamin H. Shepard, “The Queer/Gay Assimilationist: The Suits vs. the Sluts,” Monthly Review: An Independent Socialist Magazine 53:1 (May 2001): 49-63.

Further Reading:

“ 4 Policemen Hurt in ‘Village’ Raid,” The New York Times, 29 June 1969.

Duberman, Martin. 1994. Stonewall. New York: Plume.

“Hostile Crowd Dispersed Near Sheridan Square,” New York Times, 3 July 1969.

Meeker, Martin. 2001. “Behind the Mask of Respectability: Reconsidering the Mattachine Society and Male Homophile Practice, 1950s and 1960s.” Journal of the History of Sexuality. 1:78-116.

“Police Again Rout ‘Village’ Youths,” New York Times, 30 June 1969.

Sears,James T. 2001. Rebels, Rubyfruit, and Rhinestones: Queering Space in the Stonewall South. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Shepard, Benjamin H. 2001. “The Queer/Gay Assimilationist: The Suits vs. the Sluts.” Monthly Review: An Independent Socialist Magazine 53:1, 49-63.

Smith, Howard. “Full Moon Over the Stonewall,” The Village Voice, 3 July 1969.

Suran, Justin David. 2001. “Coming Out Against the War: Antimilitarism and the Politicization of Homosexuality in the Era of Vietnam.” American Quarterly 3: 452-488.

Truscott,Lucian, IV. “Gay Power Comes To Sheridan Square.” The Village Voice. 3 July 1969.

“Village Raid Stirs Melee.” New York Post. 28 June 1969.

Monday, September 20, 2010

Gay Rights Movement: Stonewall Riots

While the two movements described by Meeker and Suran are precursors of the gay liberation movement sparked by the Stonewall Riots, the most often cited catalyst of the gay liberation movement is the series of riots that began on the night of Friday, June 27, 1969, after a raid on the Stonewall Inn, which continued for the next three nights. Raids of gay bars in New York City, particularly Greenwich Village, were not uncommon in the summer of 1969, what made the raid on the Stonewall on June 27 so different was that the patrons of the bar resisted instead of going peacefully.

While the two movements described by Meeker and Suran are precursors of the gay liberation movement sparked by the Stonewall Riots, the most often cited catalyst of the gay liberation movement is the series of riots that began on the night of Friday, June 27, 1969, after a raid on the Stonewall Inn, which continued for the next three nights. Raids of gay bars in New York City, particularly Greenwich Village, were not uncommon in the summer of 1969, what made the raid on the Stonewall on June 27 so different was that the patrons of the bar resisted instead of going peacefully.  The New York Post was the first of the New York newspapers to report the raid and the first “melee” that followed the raid. The Post described the scene following the raid on the Stonewall Inn, “a tavern frequented by homosexuals at 53 Christopher St.” The raid was staged because of the unlicensed sale of liquor. On that first night twelve people were arrested with charges ranging from assault to disorderly conduct because of the impromptu riot that soon ensued. As the police drove away with those in custody from the raid, the newspaper describes how “hundreds of passerby” shouted “Gay Power” and “We Want Freedom” while laying siege to the bar with “an improvised battering ram, garbage cans, bottles and beer cans in a protest demonstration.” More police were sent to 53 Christopher Street where the disturbance raged for more than two hours.[1]

The New York Post was the first of the New York newspapers to report the raid and the first “melee” that followed the raid. The Post described the scene following the raid on the Stonewall Inn, “a tavern frequented by homosexuals at 53 Christopher St.” The raid was staged because of the unlicensed sale of liquor. On that first night twelve people were arrested with charges ranging from assault to disorderly conduct because of the impromptu riot that soon ensued. As the police drove away with those in custody from the raid, the newspaper describes how “hundreds of passerby” shouted “Gay Power” and “We Want Freedom” while laying siege to the bar with “an improvised battering ram, garbage cans, bottles and beer cans in a protest demonstration.” More police were sent to 53 Christopher Street where the disturbance raged for more than two hours.[1]  For the next two days and again on July 3, the New York Times ran small pieces about the “Village Raid.” On June 29, the Times reported that shortly after 3 a.m. on the previous day, that the bar had been raided. About two hundred patrons were thrown out of the bar and soon were joined by about two hundred more in protest of the raid. Police seized several cases of liquor from the establishment, which the police stated was operating without a liquor license. The Times reported that the “melee” lasted for only about forty-five minutes after the raid before the crowd dispersed and thirteen people in all were arrested with four policemen suffering injuries, one a broken wrist. The June 29 article also stated that the raid was one of three conducted in the last two weeks, and on the night of June 28, “throngs of young men congregated outside the inn. . .reading aloud condemnations of the police.” [2]

For the next two days and again on July 3, the New York Times ran small pieces about the “Village Raid.” On June 29, the Times reported that shortly after 3 a.m. on the previous day, that the bar had been raided. About two hundred patrons were thrown out of the bar and soon were joined by about two hundred more in protest of the raid. Police seized several cases of liquor from the establishment, which the police stated was operating without a liquor license. The Times reported that the “melee” lasted for only about forty-five minutes after the raid before the crowd dispersed and thirteen people in all were arrested with four policemen suffering injuries, one a broken wrist. The June 29 article also stated that the raid was one of three conducted in the last two weeks, and on the night of June 28, “throngs of young men congregated outside the inn. . .reading aloud condemnations of the police.” [2]  The June 30 edition of the newspaper stated that on the early morning of June 29, a crowd of about four hundred gathered again on Christopher street and a Tactical Patrol Unit was called in to control the disturbance at about 2:15 a.m. The crowd was throwing bottles and lighting small fires. With their arms linked, the police made sweeps down Christopher Street from the Avenue of the Americas to Seventh Avenue, but the crowds merely moved into side streets and reformed behind the police. Those who did not move out of the way of the police line were pushed along and two men were clubbed to the ground. Stones and bottles were thrown at the police and twice the police broke ranks to charge the crowd. Three people were arrested on charges of harassment and disorderly conduct. The June 30 article also states that the crowd gathered again on the evening of June 29 to denounce the police for “allegedly harassing homosexuals.” Graffiti painted on the boarded up windows of the inn stated “Support gay power” and “Legalize gay bars.”[3] A July 3, article in the New York Times stated that a chanting crowd of about five hundred gathered again outside the Stonewall Inn and had to be dispersed by the police, while four protestors were arrested.[4]

The June 30 edition of the newspaper stated that on the early morning of June 29, a crowd of about four hundred gathered again on Christopher street and a Tactical Patrol Unit was called in to control the disturbance at about 2:15 a.m. The crowd was throwing bottles and lighting small fires. With their arms linked, the police made sweeps down Christopher Street from the Avenue of the Americas to Seventh Avenue, but the crowds merely moved into side streets and reformed behind the police. Those who did not move out of the way of the police line were pushed along and two men were clubbed to the ground. Stones and bottles were thrown at the police and twice the police broke ranks to charge the crowd. Three people were arrested on charges of harassment and disorderly conduct. The June 30 article also states that the crowd gathered again on the evening of June 29 to denounce the police for “allegedly harassing homosexuals.” Graffiti painted on the boarded up windows of the inn stated “Support gay power” and “Legalize gay bars.”[3] A July 3, article in the New York Times stated that a chanting crowd of about five hundred gathered again outside the Stonewall Inn and had to be dispersed by the police, while four protestors were arrested.[4]  On July 3, 1969, The Village Voice published two, more substantial articles on the incidents surrounding the Stonewall Inn. Of the two articles, Lucian Trusctott IV’s article is written in a tongue-in-cheek style focusing on the several days of riots that ensued after the first raid. Truscott reports that the crowd, which returned on Saturday night, were being led by “gay power” cheers: “We are the Stonewall girls/ We wear our hair in curls/ We have no underwear/ We show our pubic hair!” The article is mostly sympathetic to the gay cause and quotes Allen Ginsberg, a gay activist, stated “Gay Power! Isn’t that great! We’re one of the largest minorities in the country--10 percent, you know. It’s about time we did something to assert ourselves.” Truscott is prophetic when he end his article by stating:

On July 3, 1969, The Village Voice published two, more substantial articles on the incidents surrounding the Stonewall Inn. Of the two articles, Lucian Trusctott IV’s article is written in a tongue-in-cheek style focusing on the several days of riots that ensued after the first raid. Truscott reports that the crowd, which returned on Saturday night, were being led by “gay power” cheers: “We are the Stonewall girls/ We wear our hair in curls/ We have no underwear/ We show our pubic hair!” The article is mostly sympathetic to the gay cause and quotes Allen Ginsberg, a gay activist, stated “Gay Power! Isn’t that great! We’re one of the largest minorities in the country--10 percent, you know. It’s about time we did something to assert ourselves.” Truscott is prophetic when he end his article by stating: We reached Cooper Square, and as Ginsberg turned to head toward home, he waved and yelled, “Defend the fairies!” and bounce on across the square. He enjoyed the prospect of “gay power” and is probably working on a manifesto for the movement right now. Watch out. The liberation is under way![5]The other article, by Howard Smith, is much more subdued. Smith, a reporter for the Voice, only relates the night of the raid, when he stayed with the police for protection. Although his article is not exactly pro-gay, Smith does offer some interesting observations that the other reports of the Stonewall Riots leave out.

First of all, Smith reports on the number of men in drag that actually fight back. All other reports in The New York Times and The New York Post only state that the young men who resisted the police were young men, but Smith states that their were men in drag and a number of lesbians who resisted the police. Smith also describes in detail the “melee” especially concerning the attack on the police wagon while he was inside with the police for protection against the mob. Lastly, Smith points out the connection with the bar being owned by the mafia, although he only states that the men who own and run the establishment are Italians. Smith does relate that statements to the police were basically: “we are just honest businessmen, who are being harassed by the police because we cater to homosexuals, and because our names are Italian so they think we are part of something bigger.”[6]

First of all, Smith reports on the number of men in drag that actually fight back. All other reports in The New York Times and The New York Post only state that the young men who resisted the police were young men, but Smith states that their were men in drag and a number of lesbians who resisted the police. Smith also describes in detail the “melee” especially concerning the attack on the police wagon while he was inside with the police for protection against the mob. Lastly, Smith points out the connection with the bar being owned by the mafia, although he only states that the men who own and run the establishment are Italians. Smith does relate that statements to the police were basically: “we are just honest businessmen, who are being harassed by the police because we cater to homosexuals, and because our names are Italian so they think we are part of something bigger.”[6]  While the newspapers provide a glimpse at the reaction of the New York press as the riots were happening, several further accounts were later retold in memoirs of the Riot. The most thorough account is given by Martin Duberman in his book Stonewall. Mostly through oral history interviews, Duberman is able to relate the events of the Stonewall Riots with more accuracy than the accounts in the New York City newspapers.

While the newspapers provide a glimpse at the reaction of the New York press as the riots were happening, several further accounts were later retold in memoirs of the Riot. The most thorough account is given by Martin Duberman in his book Stonewall. Mostly through oral history interviews, Duberman is able to relate the events of the Stonewall Riots with more accuracy than the accounts in the New York City newspapers. No one really knows what set off the “flash of anger” that began the riots. Most of the people who were there just say that all of a sudden the crowd grew angry and either began throwing bottles or trying to free one of the men in drag who were being arrested.[7] Even if it cannot be determined what set off the anger that went through the crowd, it must be asked, why that night.

Many factors could have contributed to why the people in the Stonewall Inn fought back. It could have been because most of them had reached their breaking point, with the criminalization of their behavior to the Vietnam War that had raged for the last four years in the living rooms of every American with a television. One interesting theory could be that with Judy Garland’s funeral earlier that day, the men in the Stonewall Inn were distraught over losing their greatest icon. Probably what compounded most of the anger that rushed through the crowd was that most of the patrons were high on some type of drugs.[8] Another factor was that the raid occurred early in the morning. Usually raids happened earlier in the evening so that the bar could open back up. Police were being bribed, so raids were rarely major incidents.[9]

Many factors could have contributed to why the people in the Stonewall Inn fought back. It could have been because most of them had reached their breaking point, with the criminalization of their behavior to the Vietnam War that had raged for the last four years in the living rooms of every American with a television. One interesting theory could be that with Judy Garland’s funeral earlier that day, the men in the Stonewall Inn were distraught over losing their greatest icon. Probably what compounded most of the anger that rushed through the crowd was that most of the patrons were high on some type of drugs.[8] Another factor was that the raid occurred early in the morning. Usually raids happened earlier in the evening so that the bar could open back up. Police were being bribed, so raids were rarely major incidents.[9] Once the crowd did begin to fight back, the fervor of rebellion and the feeling that a revolution was happening among the gay community swept through the crowd.[10] No longer were gays going to work with the system to make themselves feel more normal. They wanted to be accepted for who they were, not for who the establishment wanted them to be. African-Americans had made great strides in their civil rights struggle, and women were just beginning to make strides for women’s liberation and equality. As pointed out by Alan Ginsberg earlier, gays and lesbians were a large minority in the United States. If they could make themselves heard, this could change everything for them. No longer would they be forced to only socialize with each other in dank and dingy, mafia owned bars, that could be raided at anytime and served watered down drinks so the owners could make more money. The law in New York City stated that a person must wear at least three articles of clothing appropriate to one’s own gender.[11] Gay bars were not allowed to have a liquor license and most were not allowed to have dancing.

“[1]Village Raid Stirs Melee,” New York Post, 28 June 1969.

“[2]4 Policemen Hurt in ‘Village’ Raid,” The New York Times, 29 June 1969, 33.

“[3]Police Again Rout ‘Village’ Youths,” New York Times, 30 June 1969, 22.

“[4]Hostile Crowd Dispersed Near Sheridan Square,” New York Times, 3 July 1969.

[5]Lucian Truscott IV, “Gay Power Comes To Sheridan Square,” The Village Voice, 3 July 1969, 18.

[6]Howard Smith, “Full Moon Over the Stonewall,” The Village Voice, 3 July 1969, 25.

[7]Martin Duberman, Stonewall, (New York: Plume, 1994), 196-197.

[8]Ibid., 181-196.

[9]Ibid., 194-195.

[10]Ibid., 198.

[11]Ibid., 196.

Friday, September 17, 2010

Gay Rights Movement: The Anti-War Movement

For some more information about the history of Gays in the Military, check out this article from Time Magazine: Brief History of Gays in the Military.

In more modern times, the United States and most countries of the world criminalized homosexuality (sodomy) and therefore banned gay men and women from serving in the military. The Mattachine Society, founded in 1950, was one of the earliest homophile (gay rights) organizations in the United States, probably second only to Chicago’s short-lived Society for Human Rights (1924). Harry Hay and a group of Los Angeles male friends formed the group to protect and improve the rights of homosexuals. Because of concerns for secrecy and the founders’ leftist ideology, they adopted the cell organization of the Communist Party. In the anti-Communist atmosphere of the 1950s, the Society’s growing membership substituted a more traditional ameliorative civil rights leadership style and agenda for the group’s early Communist model. Then as branches formed in other cities, the Society splintered in regional groups by 1961.

In more modern times, the United States and most countries of the world criminalized homosexuality (sodomy) and therefore banned gay men and women from serving in the military. The Mattachine Society, founded in 1950, was one of the earliest homophile (gay rights) organizations in the United States, probably second only to Chicago’s short-lived Society for Human Rights (1924). Harry Hay and a group of Los Angeles male friends formed the group to protect and improve the rights of homosexuals. Because of concerns for secrecy and the founders’ leftist ideology, they adopted the cell organization of the Communist Party. In the anti-Communist atmosphere of the 1950s, the Society’s growing membership substituted a more traditional ameliorative civil rights leadership style and agenda for the group’s early Communist model. Then as branches formed in other cities, the Society splintered in regional groups by 1961.Youths rebelled against older homophile organization, which often refused to take a stance on the Vietnam War. Young gay men had to chose whether or not to reveal or conceal their homosexuality when they came before the draft

board, because with the draft board being composed of local citizens, this could mean being outed to friends, neighbors or parents. The dilemma faced by gay youths polarized the gay liberation movement and gay youths joined in on the antiwar protests.[1] While older homophile organizations saw non-participation of homosexuals in the American military as detrimental to gay rights, youths of the antiwar stance saw it as a positive good. Suran contends that there are four major assertions by gay men in the antiwar movement. First, young homophiles saw military service as politically and morally counterproductive. Second, they declared war as a masculine affront to gay men. They cited the “effiminist” nature of homosexual men and refused to participate in macho role playing. Third, the young activists viewed imperialism as an extension of heterosexist ideology. Finally, they perceived homosexuality itself as antiwar antiestablishment, and anti-imperialist. With these four beliefs, young homophiles refused to embrace the older homophile tradition of assimilation in to “normal” society through military service.[2]

board, because with the draft board being composed of local citizens, this could mean being outed to friends, neighbors or parents. The dilemma faced by gay youths polarized the gay liberation movement and gay youths joined in on the antiwar protests.[1] While older homophile organizations saw non-participation of homosexuals in the American military as detrimental to gay rights, youths of the antiwar stance saw it as a positive good. Suran contends that there are four major assertions by gay men in the antiwar movement. First, young homophiles saw military service as politically and morally counterproductive. Second, they declared war as a masculine affront to gay men. They cited the “effiminist” nature of homosexual men and refused to participate in macho role playing. Third, the young activists viewed imperialism as an extension of heterosexist ideology. Finally, they perceived homosexuality itself as antiwar antiestablishment, and anti-imperialist. With these four beliefs, young homophiles refused to embrace the older homophile tradition of assimilation in to “normal” society through military service.[2]  Though the Mattachine Society fell apart by the 1970s, one of their focuses was on protesting the US policy against gays serving in the military. They believed they could serve their country in any capacity, whether it be in government (gay men and women were not allowed to serve in government positions because their sexuality could be used as a basis for blackmail by communist spies) or in the military.

Though the Mattachine Society fell apart by the 1970s, one of their focuses was on protesting the US policy against gays serving in the military. They believed they could serve their country in any capacity, whether it be in government (gay men and women were not allowed to serve in government positions because their sexuality could be used as a basis for blackmail by communist spies) or in the military.When more public gay rights groups formed after the 1969 Stonewall Riots,

gay men had moved away from support for military service. With the Vietnam War and the draft still very much a reality, gay rights groups turned their backs on the issue of military service because they did not want to be drafted. However, the government also turned their backs on the ban and forced many gay men who were drafted to serve, deciding that they needed the manpower more than they needed to uphold the ban on military service. In the United States today, sodomy is no longer illegal thanks to the Supreme Court decision, Lawrence v. Texas, and in 1973 the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Therefore there is no legal or medical reason that can be used to deny gay men and women the right to serve openly in the military.

gay men had moved away from support for military service. With the Vietnam War and the draft still very much a reality, gay rights groups turned their backs on the issue of military service because they did not want to be drafted. However, the government also turned their backs on the ban and forced many gay men who were drafted to serve, deciding that they needed the manpower more than they needed to uphold the ban on military service. In the United States today, sodomy is no longer illegal thanks to the Supreme Court decision, Lawrence v. Texas, and in 1973 the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Therefore there is no legal or medical reason that can be used to deny gay men and women the right to serve openly in the military.

[1]Justin David Suran, “Coming Out Against the War: Antimilitarism and the Politicization of Homosexuality in the Era of Vietnam,” American Quarterly 53, no. 3 (2001): 453.

[2]Ibid., 471-472.

Next: The Stonewall Riots

Monday, September 13, 2010

Gay Rights Movement: Introduction

The summer of 1969 showed the best and worst of America. In June, President Nixon announced Vietnamization as a way to get America out of

the Vietnam War, which reminds me a lot of our present policy of Iraqization of the now (supposedly) ended war in Iraq. Man stood on the moon for the first time on July 16 with the Apollo 11 landing. In August, Woodstock demonstrated to the world the epitome of the flower children’s culture and the height of the counter culture movement. While such events were celebrated in American culture, the summer of 1969 was also marked by a series of tragedies. Judy Garland died from an overdose of drugs. The Manson Family murdered actress Sharon Tate, her unborn child, and four others in Bel Air, California, in what has

the Vietnam War, which reminds me a lot of our present policy of Iraqization of the now (supposedly) ended war in Iraq. Man stood on the moon for the first time on July 16 with the Apollo 11 landing. In August, Woodstock demonstrated to the world the epitome of the flower children’s culture and the height of the counter culture movement. While such events were celebrated in American culture, the summer of 1969 was also marked by a series of tragedies. Judy Garland died from an overdose of drugs. The Manson Family murdered actress Sharon Tate, her unborn child, and four others in Bel Air, California, in what has  become known as Helter Skelter. Mary Jo Kopechne died in a drunk driving accident with Ted Kennedy in Chapppaquiddick, Massachusetts. And 248 people perished in Mississippi when Hurricane Camille crashed into the Gulf Coast. The Civil Rights Movement was also going through a change. With the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. in Memphis in 1968, the end had come to the classic period of the Civil Rights Movement. The movement was becoming more radical and began to splinter off into more groups of people, including women and the gay and lesbian community.

become known as Helter Skelter. Mary Jo Kopechne died in a drunk driving accident with Ted Kennedy in Chapppaquiddick, Massachusetts. And 248 people perished in Mississippi when Hurricane Camille crashed into the Gulf Coast. The Civil Rights Movement was also going through a change. With the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. in Memphis in 1968, the end had come to the classic period of the Civil Rights Movement. The movement was becoming more radical and began to splinter off into more groups of people, including women and the gay and lesbian community. With the Stonewall Riots, the modern gay and lesbian rights movement had its beginnings in Greenwich Village, New York, during the summer of 1969.

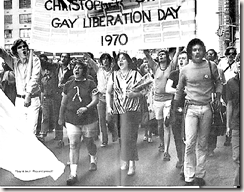

The Stonewall Riots marked a change in the direction of the gay liberation movement that had been brewing since the end of World War II with the founding of the Mattachine Society in Los Angeles with chapters in New York, Philadelphia, and San Francisco. Gays and lesbians worked with the Civil Rights Movement, participated in the anti-war movement, and kept their sexuality in the background. But the “Friends of Dorothy” and “Daughters of Bilitis” were determined to no longer stay in the background and have homosexuality criminalized as it had been in the past. On the night of June 27, 1969, the gays and lesbians in the Stonewall Inn fought back after a police raid, and the modern gay liberation movement was born and would continue to grow as gay pride marches marked the subsequent anniversaries of the Stonewall Riots each year in New York during the month of June.

The Stonewall Riots marked a change in the direction of the gay liberation movement that had been brewing since the end of World War II with the founding of the Mattachine Society in Los Angeles with chapters in New York, Philadelphia, and San Francisco. Gays and lesbians worked with the Civil Rights Movement, participated in the anti-war movement, and kept their sexuality in the background. But the “Friends of Dorothy” and “Daughters of Bilitis” were determined to no longer stay in the background and have homosexuality criminalized as it had been in the past. On the night of June 27, 1969, the gays and lesbians in the Stonewall Inn fought back after a police raid, and the modern gay liberation movement was born and would continue to grow as gay pride marches marked the subsequent anniversaries of the Stonewall Riots each year in New York during the month of June. Although most historians of the gay liberation movement place the climax of

the beginning of the modern movement on the Stonewall Riots, some west coast historians give the metropolitan centers of the movement as Los Angeles and San Francisco in the fifties with the founding of the Mattachine Society, the earliest homophile activist organization, and the antiwar movement in San Francisco during the sixties. Martin Meeker of the University of Southern California presented a re-evaluation of the Mattachine Society in his article “Behind the Mask of Respectability: Reconsidering the Mattachine Society and Male Homophile Practice 1950s and 1960s,” and Justin David Suran of the University of California, Berkeley examines the effects of the Vietnam War on the gay liberation movement in “Coming Out Against the War: Antimilitarism and the Politicization of Homosexuality in the Era of Vietnam.”

the beginning of the modern movement on the Stonewall Riots, some west coast historians give the metropolitan centers of the movement as Los Angeles and San Francisco in the fifties with the founding of the Mattachine Society, the earliest homophile activist organization, and the antiwar movement in San Francisco during the sixties. Martin Meeker of the University of Southern California presented a re-evaluation of the Mattachine Society in his article “Behind the Mask of Respectability: Reconsidering the Mattachine Society and Male Homophile Practice 1950s and 1960s,” and Justin David Suran of the University of California, Berkeley examines the effects of the Vietnam War on the gay liberation movement in “Coming Out Against the War: Antimilitarism and the Politicization of Homosexuality in the Era of Vietnam.” Next: The Mattacine Society

Announcement: I have decided that I will try something new with The Closet Professor. Most college classes either meet on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays or on Tuesdays and Thursdays. Therefore, I have decided that The Closet Professor, which has a very loyal but also relatively small following, will begin posting only on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. These posts take more time to put together than the posts on my other blog, so I have chosen to give you quality not quantity. I love this blog, and it is the blog I love to do: teach. I hope that you will continue to read and comment as the posts slow down just a bit. Occasionally, I will randomly post things for other days as the mood strikes but for now, I plan to follow the new schedule.

Thanks for reading.