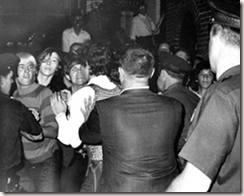

While the two movements described by Meeker and Suran are precursors of the gay liberation movement sparked by the Stonewall Riots, the most often cited catalyst of the gay liberation movement is the series of riots that began on the night of Friday, June 27, 1969, after a raid on the Stonewall Inn, which continued for the next three nights. Raids of gay bars in New York City, particularly Greenwich Village, were not uncommon in the summer of 1969, what made the raid on the Stonewall on June 27 so different was that the patrons of the bar resisted instead of going peacefully.

While the two movements described by Meeker and Suran are precursors of the gay liberation movement sparked by the Stonewall Riots, the most often cited catalyst of the gay liberation movement is the series of riots that began on the night of Friday, June 27, 1969, after a raid on the Stonewall Inn, which continued for the next three nights. Raids of gay bars in New York City, particularly Greenwich Village, were not uncommon in the summer of 1969, what made the raid on the Stonewall on June 27 so different was that the patrons of the bar resisted instead of going peacefully.  The New York Post was the first of the New York newspapers to report the raid and the first “melee” that followed the raid. The Post described the scene following the raid on the Stonewall Inn, “a tavern frequented by homosexuals at 53 Christopher St.” The raid was staged because of the unlicensed sale of liquor. On that first night twelve people were arrested with charges ranging from assault to disorderly conduct because of the impromptu riot that soon ensued. As the police drove away with those in custody from the raid, the newspaper describes how “hundreds of passerby” shouted “Gay Power” and “We Want Freedom” while laying siege to the bar with “an improvised battering ram, garbage cans, bottles and beer cans in a protest demonstration.” More police were sent to 53 Christopher Street where the disturbance raged for more than two hours.[1]

The New York Post was the first of the New York newspapers to report the raid and the first “melee” that followed the raid. The Post described the scene following the raid on the Stonewall Inn, “a tavern frequented by homosexuals at 53 Christopher St.” The raid was staged because of the unlicensed sale of liquor. On that first night twelve people were arrested with charges ranging from assault to disorderly conduct because of the impromptu riot that soon ensued. As the police drove away with those in custody from the raid, the newspaper describes how “hundreds of passerby” shouted “Gay Power” and “We Want Freedom” while laying siege to the bar with “an improvised battering ram, garbage cans, bottles and beer cans in a protest demonstration.” More police were sent to 53 Christopher Street where the disturbance raged for more than two hours.[1]  For the next two days and again on July 3, the New York Times ran small pieces about the “Village Raid.” On June 29, the Times reported that shortly after 3 a.m. on the previous day, that the bar had been raided. About two hundred patrons were thrown out of the bar and soon were joined by about two hundred more in protest of the raid. Police seized several cases of liquor from the establishment, which the police stated was operating without a liquor license. The Times reported that the “melee” lasted for only about forty-five minutes after the raid before the crowd dispersed and thirteen people in all were arrested with four policemen suffering injuries, one a broken wrist. The June 29 article also stated that the raid was one of three conducted in the last two weeks, and on the night of June 28, “throngs of young men congregated outside the inn. . .reading aloud condemnations of the police.” [2]

For the next two days and again on July 3, the New York Times ran small pieces about the “Village Raid.” On June 29, the Times reported that shortly after 3 a.m. on the previous day, that the bar had been raided. About two hundred patrons were thrown out of the bar and soon were joined by about two hundred more in protest of the raid. Police seized several cases of liquor from the establishment, which the police stated was operating without a liquor license. The Times reported that the “melee” lasted for only about forty-five minutes after the raid before the crowd dispersed and thirteen people in all were arrested with four policemen suffering injuries, one a broken wrist. The June 29 article also stated that the raid was one of three conducted in the last two weeks, and on the night of June 28, “throngs of young men congregated outside the inn. . .reading aloud condemnations of the police.” [2]  The June 30 edition of the newspaper stated that on the early morning of June 29, a crowd of about four hundred gathered again on Christopher street and a Tactical Patrol Unit was called in to control the disturbance at about 2:15 a.m. The crowd was throwing bottles and lighting small fires. With their arms linked, the police made sweeps down Christopher Street from the Avenue of the Americas to Seventh Avenue, but the crowds merely moved into side streets and reformed behind the police. Those who did not move out of the way of the police line were pushed along and two men were clubbed to the ground. Stones and bottles were thrown at the police and twice the police broke ranks to charge the crowd. Three people were arrested on charges of harassment and disorderly conduct. The June 30 article also states that the crowd gathered again on the evening of June 29 to denounce the police for “allegedly harassing homosexuals.” Graffiti painted on the boarded up windows of the inn stated “Support gay power” and “Legalize gay bars.”[3] A July 3, article in the New York Times stated that a chanting crowd of about five hundred gathered again outside the Stonewall Inn and had to be dispersed by the police, while four protestors were arrested.[4]

The June 30 edition of the newspaper stated that on the early morning of June 29, a crowd of about four hundred gathered again on Christopher street and a Tactical Patrol Unit was called in to control the disturbance at about 2:15 a.m. The crowd was throwing bottles and lighting small fires. With their arms linked, the police made sweeps down Christopher Street from the Avenue of the Americas to Seventh Avenue, but the crowds merely moved into side streets and reformed behind the police. Those who did not move out of the way of the police line were pushed along and two men were clubbed to the ground. Stones and bottles were thrown at the police and twice the police broke ranks to charge the crowd. Three people were arrested on charges of harassment and disorderly conduct. The June 30 article also states that the crowd gathered again on the evening of June 29 to denounce the police for “allegedly harassing homosexuals.” Graffiti painted on the boarded up windows of the inn stated “Support gay power” and “Legalize gay bars.”[3] A July 3, article in the New York Times stated that a chanting crowd of about five hundred gathered again outside the Stonewall Inn and had to be dispersed by the police, while four protestors were arrested.[4]  On July 3, 1969, The Village Voice published two, more substantial articles on the incidents surrounding the Stonewall Inn. Of the two articles, Lucian Trusctott IV’s article is written in a tongue-in-cheek style focusing on the several days of riots that ensued after the first raid. Truscott reports that the crowd, which returned on Saturday night, were being led by “gay power” cheers: “We are the Stonewall girls/ We wear our hair in curls/ We have no underwear/ We show our pubic hair!” The article is mostly sympathetic to the gay cause and quotes Allen Ginsberg, a gay activist, stated “Gay Power! Isn’t that great! We’re one of the largest minorities in the country--10 percent, you know. It’s about time we did something to assert ourselves.” Truscott is prophetic when he end his article by stating:

On July 3, 1969, The Village Voice published two, more substantial articles on the incidents surrounding the Stonewall Inn. Of the two articles, Lucian Trusctott IV’s article is written in a tongue-in-cheek style focusing on the several days of riots that ensued after the first raid. Truscott reports that the crowd, which returned on Saturday night, were being led by “gay power” cheers: “We are the Stonewall girls/ We wear our hair in curls/ We have no underwear/ We show our pubic hair!” The article is mostly sympathetic to the gay cause and quotes Allen Ginsberg, a gay activist, stated “Gay Power! Isn’t that great! We’re one of the largest minorities in the country--10 percent, you know. It’s about time we did something to assert ourselves.” Truscott is prophetic when he end his article by stating: We reached Cooper Square, and as Ginsberg turned to head toward home, he waved and yelled, “Defend the fairies!” and bounce on across the square. He enjoyed the prospect of “gay power” and is probably working on a manifesto for the movement right now. Watch out. The liberation is under way![5]The other article, by Howard Smith, is much more subdued. Smith, a reporter for the Voice, only relates the night of the raid, when he stayed with the police for protection. Although his article is not exactly pro-gay, Smith does offer some interesting observations that the other reports of the Stonewall Riots leave out.

First of all, Smith reports on the number of men in drag that actually fight back. All other reports in The New York Times and The New York Post only state that the young men who resisted the police were young men, but Smith states that their were men in drag and a number of lesbians who resisted the police. Smith also describes in detail the “melee” especially concerning the attack on the police wagon while he was inside with the police for protection against the mob. Lastly, Smith points out the connection with the bar being owned by the mafia, although he only states that the men who own and run the establishment are Italians. Smith does relate that statements to the police were basically: “we are just honest businessmen, who are being harassed by the police because we cater to homosexuals, and because our names are Italian so they think we are part of something bigger.”[6]

First of all, Smith reports on the number of men in drag that actually fight back. All other reports in The New York Times and The New York Post only state that the young men who resisted the police were young men, but Smith states that their were men in drag and a number of lesbians who resisted the police. Smith also describes in detail the “melee” especially concerning the attack on the police wagon while he was inside with the police for protection against the mob. Lastly, Smith points out the connection with the bar being owned by the mafia, although he only states that the men who own and run the establishment are Italians. Smith does relate that statements to the police were basically: “we are just honest businessmen, who are being harassed by the police because we cater to homosexuals, and because our names are Italian so they think we are part of something bigger.”[6]  While the newspapers provide a glimpse at the reaction of the New York press as the riots were happening, several further accounts were later retold in memoirs of the Riot. The most thorough account is given by Martin Duberman in his book Stonewall. Mostly through oral history interviews, Duberman is able to relate the events of the Stonewall Riots with more accuracy than the accounts in the New York City newspapers.

While the newspapers provide a glimpse at the reaction of the New York press as the riots were happening, several further accounts were later retold in memoirs of the Riot. The most thorough account is given by Martin Duberman in his book Stonewall. Mostly through oral history interviews, Duberman is able to relate the events of the Stonewall Riots with more accuracy than the accounts in the New York City newspapers. No one really knows what set off the “flash of anger” that began the riots. Most of the people who were there just say that all of a sudden the crowd grew angry and either began throwing bottles or trying to free one of the men in drag who were being arrested.[7] Even if it cannot be determined what set off the anger that went through the crowd, it must be asked, why that night.

Many factors could have contributed to why the people in the Stonewall Inn fought back. It could have been because most of them had reached their breaking point, with the criminalization of their behavior to the Vietnam War that had raged for the last four years in the living rooms of every American with a television. One interesting theory could be that with Judy Garland’s funeral earlier that day, the men in the Stonewall Inn were distraught over losing their greatest icon. Probably what compounded most of the anger that rushed through the crowd was that most of the patrons were high on some type of drugs.[8] Another factor was that the raid occurred early in the morning. Usually raids happened earlier in the evening so that the bar could open back up. Police were being bribed, so raids were rarely major incidents.[9]

Many factors could have contributed to why the people in the Stonewall Inn fought back. It could have been because most of them had reached their breaking point, with the criminalization of their behavior to the Vietnam War that had raged for the last four years in the living rooms of every American with a television. One interesting theory could be that with Judy Garland’s funeral earlier that day, the men in the Stonewall Inn were distraught over losing their greatest icon. Probably what compounded most of the anger that rushed through the crowd was that most of the patrons were high on some type of drugs.[8] Another factor was that the raid occurred early in the morning. Usually raids happened earlier in the evening so that the bar could open back up. Police were being bribed, so raids were rarely major incidents.[9] Once the crowd did begin to fight back, the fervor of rebellion and the feeling that a revolution was happening among the gay community swept through the crowd.[10] No longer were gays going to work with the system to make themselves feel more normal. They wanted to be accepted for who they were, not for who the establishment wanted them to be. African-Americans had made great strides in their civil rights struggle, and women were just beginning to make strides for women’s liberation and equality. As pointed out by Alan Ginsberg earlier, gays and lesbians were a large minority in the United States. If they could make themselves heard, this could change everything for them. No longer would they be forced to only socialize with each other in dank and dingy, mafia owned bars, that could be raided at anytime and served watered down drinks so the owners could make more money. The law in New York City stated that a person must wear at least three articles of clothing appropriate to one’s own gender.[11] Gay bars were not allowed to have a liquor license and most were not allowed to have dancing.

“[1]Village Raid Stirs Melee,” New York Post, 28 June 1969.

“[2]4 Policemen Hurt in ‘Village’ Raid,” The New York Times, 29 June 1969, 33.

“[3]Police Again Rout ‘Village’ Youths,” New York Times, 30 June 1969, 22.

“[4]Hostile Crowd Dispersed Near Sheridan Square,” New York Times, 3 July 1969.

[5]Lucian Truscott IV, “Gay Power Comes To Sheridan Square,” The Village Voice, 3 July 1969, 18.

[6]Howard Smith, “Full Moon Over the Stonewall,” The Village Voice, 3 July 1969, 25.

[7]Martin Duberman, Stonewall, (New York: Plume, 1994), 196-197.

[8]Ibid., 181-196.

[9]Ibid., 194-195.

[10]Ibid., 198.

[11]Ibid., 196.

6 comments:

Joe: An important beginning that little did people know at the time that they were making history. The debt we owe them is immeasurable.

The gay rights movement began much like most gay kids lives and the school bully. We take and take and take, and then one day we can't take it anymore and we fight back. The Stonewall Riots were somewhat successful and got the ball rolling, but we can't become complacent and we have to keep fighting.

Joe,

Do you know when the term "gay" was first used to describe homosexuals? And how did it come about?

Uncutplus: I know that for most of the history of the Judeo-Christian world the term sodomite has most often been used. By the 19th century, the terms homophile, and later, homosexual were used, but after I little research it appears that the term gay took on a sexual connotation in the 17th century meaning that the person was "uninhibited by moral constraints" most often as a substitute for prostitute or a womanizer. As for it meaning for homosexual, it seems that this usage of the word begins in the 1920s, probably with the lost generation and writers such as Gertrude Stein. During the 19th century it meant someone who disregarded sexual mores and could mean a homosexual, but it is not until the 20th century that this meaning grows in popularity.

Interestingly enough, it is because so few terms were used to mean homosexual (except sodomite and a few others in non-western cultures) that some historians argue that homosexuality today is not the same as it was throughout most of history. I tend to disagree and believe that it has always been the same, but the ability to be openly devoted to one person of the same gender was just not available and could and did often lead to death of the people involved in such a relationship.

Thanks, Joe. When growing up in the 1950s, I remember "queer", "sissy" and "faggot" being used, but I do not remember "gay" being used until about the mid 1960s. Perhaps it was Stonewall that began to make the term more popular.

Uncutplus, I think this would make a good post. I might have to do a post on the etymology of gay phrases and terms.

Post a Comment