He’d been sitting in the café since ten-thirty

He’d been sitting in the café since ten-thirtyexpecting him to turn up any minute.

Midnight went by, and he was still waiting for him.

It was now after one-thirty, and the café was almost deserted.

He’d grown tired of reading newspapers

mechanically. Of his three lonely shillings

only one was left: waiting that long,

he’d spent the others on coffees and brandy.

He’d smoked all his cigarettes.

So much waiting had worn him out. Because

alone like that for so many hours,

he’d also begun to have disturbing thoughts

about the immoral life he was living.

But when he saw his friend come in—

weariness, boredom, thoughts vanished at once.

His friend brought unexpected news.

He’d won sixty pounds playing cards.

Their good looks, their exquisite youthfulness,

the sensitive love they shared

were refreshed, livened, invigorated

by the sixty pounds from the card table.

Now all joy and vitality, feeling and charm,

they went—not to the homes of their respectable families

(where they were no longer wanted anyway)—

they went to a familiar and very special

house of debauchery, and they asked for a bedroom

and expensive drinks, and they drank again.

And when the expensive drinks were finished

and it was close to four in the morning,

happy, they gave themselves to love.

Following the Recipe of Ancient Greco-Syrian Magicians

Said an aesthete: “What distillation from magic herbs

Said an aesthete: “What distillation from magic herbscan I find—what distillation, following the recipe

of ancient Greco-Syrian magicians—

that will bring back to me for one day (if its power

doesn’t last longer) or even for a few hours,

my twenty-third year,

bring back to me my friend of twenty-two,

his beauty, his love.

What distillation, following the recipe

of ancient Greco-Syrian magicians, can be found

to bring back also—as part of this return of things past—

even the little room we shared.”

In an Old Book

Forgotten between the leaves of an old book—

Forgotten between the leaves of an old book—almost a hundred years old—

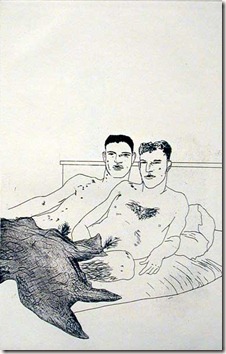

I found an unsigned watercolor.

It must have been the work of a powerful artist.

Its title: “Representation of Love.”

“...love of extreme sensualists” would have been more to the point.

Because it became clear as you looked at the work

(it was easy to see what the artist had in mind)

that the young man in the painting

was not designated for those

who love in ways that are more or less healthy,

inside the bounds of what is clearly permissible—

with his deep chestnut eyes,

the rare beauty of his face,

the beauty of anomalous charm,

with those ideal lips that bring

sensual delight to the body loved,

those ideal limbs shaped for beds

that common morality calls shameless.

In the Boring Village

In the boring village where he works—

In the boring village where he works—clerk in a textile shop, very young—

and where he’s waiting out the two or three months ahead,

another two or three months until business falls off

so he can leave for the city and plunge headlong

into its action, its entertainment;

in the boring village where he’s waiting out the time—

he goes to bed tonight full of sexual longing,

all his youth on fire with the body’s passion,

his lovely youth given over to a fine intensity.

And in his sleep pleasure comes to him;

in his sleep he sees and has the figure, the flesh he longed for...

Their Beginning

Their illicit pleasure has been fulfilled.

Their illicit pleasure has been fulfilled.They get up and dress quickly, without a word.

They come out of the house separately, furtively;

and as they move along the street a bit unsettled,

it seems they sense that something about them betrays

what kind of bed they’ve just been lying on.

But what profit for the life of the artist:

tomorrow, the day after, or years later, he’ll give voice

to the strong lines that had their beginning here.

One Night

The room was cheap and sordid,

The room was cheap and sordid,hidden above the suspect taverna.

From the window you could see the alley,

dirty and narrow. From below

came the voices of workmen

playing cards, enjoying themselves.

And there on that common, humble bed

I had love’s body, had those intoxicating lips,

red and sensual,

red lips of such intoxication

that now as I write, after so many years,

in my lonely house, I’m drunk with passion again.

In Despair

He lost him completely. And he now tries to find

He lost him completely. And he now tries to findhis lips in the lips of each new lover,

he tries in the union with each new lover

to convince himself that it’s the same young man,

that it’s to him he gives himself.

He lost him completely, as though he never existed.

He wanted, his lover said, to save himself

from the tainted, unhealthy form of sexual pleasure,

the tainted, shameful form of sexual pleasure.

There was still time, he said, to save himself.

He lost him completely, as though he never existed.

Through fantasy, through hallucination,

he tries to find his lips in the lips of other young men,

he longs to feel his kind of love once more.

David Hockney has enjoyed international fame ever since the early 1960s. He began his artistic training in 1953 to 1957 at the Bradford College of Art and continued studying at the Royal College of Art in London from 1959 to 1962. He exhibited his first works in 1960 and participated in the exhibition of the 'London Group 1960' in 1960 and was also presented for the first time with the 'Young Contemporaries' at the R.B.A. Galleries in London. He was awarded the Royal College Drawing Prize in the year he graduated. Hockney began working on his first engraved cycle 'A Rake's Progress' as early as in 1961 - it was published in 1963. Hockney traveled to New York, Berlin and Egypt after having finished his studies, in order to find ideas for his illustrations. His friend, Henry Geldzahler, the curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, encouraged him to move to Los Angeles in 1964. Hockney was offered a teaching post at the University of Iowa in the summer of the same year. His first one-man exhibition in the USA was successfully opened in the same year at the Alan Gallery in New York. He had other teaching posts until 1967 at the University of Colorado in Boulder, in Los Angeles and in Berkeley.

Hockney came across the Greek poet Konstantinos Kavafis, also called Cafavy, as early as in his studies. He was fascinated by Cafavy's clear and unpretentious way of writing about homosexuality. Thus the idea for a cycle of etchings was born, which was, however, not solely due to his fascination for the Greek poet, but also because of his basic desire to create literature etchings. The project was not put into practice before 1966, as the translation of the poems which was in existence then could not be used for legal reasons. This is why Hockney decided to entrust his friend Stephen Spender, an English poet, and his colleague Nikos Stangos with a new translation of the poems. The project was completed in just 6 months. In general, the works of the cycle were not intended to be exact illustrations of the poem, but rather visual interpretations of Cafy's poetry.

Hockney accepted a post as a guest professor at the Kunsthochschule in Hamburg in 1969. His international fame increased with his invitations to exhibit at the documenta 4 and 6 in Kassel in 1968 and 1977. He made numerous stage stets for ballets and operas by Mozart, Strawinsky, Wagner and Strauss from the mid 1970s to the 1990s. In 1982 Hockney began making Polaroid collages in a Cubist manner. He also began making color-copy prints, abstract computer graphics and fax drawings at the end of the 1980s. Hockney is often associated with Pop-Art, but he refuses to accept this labeling of his art.

Sources:

I only used seven of the fourteen poems featured in Hockney’s work, but these were the seven I found most intriguing. Each of the above poems were translated by Edmund Keeley/Philip Sherrard. In Hockey’s book, they were translated by Stephen Spender and Nikos Stangos.

No comments:

Post a Comment