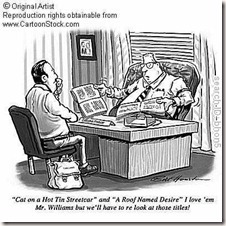

One hundred years ago today, Edwina and Cornelius Williams gave birth to Thomas Lanier Williams III in Columbus, Mississippi. Tom Williams grew up to become the greatest American playwright of the 20th century and is known to us today as Tennessee Williams. Williams is my personal favorite playwright. His plays, A Streetcar Named Desire, Suddenly, Last Summer, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, The Night of the Iguana, The Glass Menagerie, and his novel, The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone have inspired countless productions, numerous movies, and a host of enjoyment for millions. The richness of his stories, though set in a time before my birth, are timeless and never lose their appeal.

One hundred years ago today, Edwina and Cornelius Williams gave birth to Thomas Lanier Williams III in Columbus, Mississippi. Tom Williams grew up to become the greatest American playwright of the 20th century and is known to us today as Tennessee Williams. Williams is my personal favorite playwright. His plays, A Streetcar Named Desire, Suddenly, Last Summer, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, The Night of the Iguana, The Glass Menagerie, and his novel, The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone have inspired countless productions, numerous movies, and a host of enjoyment for millions. The richness of his stories, though set in a time before my birth, are timeless and never lose their appeal.Tennessee was close to his sister Rose, who was a slim and beautiful woman with a host of mental illnesses from a young age, including schizophrenia, for which she was later institutionalized and spent most of her adult life in mental hospitals. After various unsuccessful attempts at therapy, her parents eventually allowed a prefrontal lobotomy in an effort to treat her. The operation, performed in 1943, in Washington, D.C., went badly, and Rose remained incapacitated for the rest of her life. Rose's failed lobotomy was a hard blow to Tennessee, who never forgave his parents for allowing the operation. It may have been one of the factors that drove him to alcoholism.

Characters in his plays are often seen to be direct representations of his family members. Laura Wingfield in The Glass Menagerie is understood to be modeled on Rose. Some biographers say that the character of Blanche DuBois in A Streetcar Named Desire is based on her as well. The motif of lobotomy also arises in Suddenly Last Summer. Amanda Wingfield in The Glass Menagerie can easily be seen to represent his mother. Many of his characters are autobiographical, including Tom Wingfield in The Glass Menagerie and Sebastian in Suddenly Last Summer.

Characters in his plays are often seen to be direct representations of his family members. Laura Wingfield in The Glass Menagerie is understood to be modeled on Rose. Some biographers say that the character of Blanche DuBois in A Streetcar Named Desire is based on her as well. The motif of lobotomy also arises in Suddenly Last Summer. Amanda Wingfield in The Glass Menagerie can easily be seen to represent his mother. Many of his characters are autobiographical, including Tom Wingfield in The Glass Menagerie and Sebastian in Suddenly Last Summer. In his memoirs, the playwright claims he became sexually active as a teenager; his biographer Lyle Leverich maintained this actually occurred later, in his late 20s. His first sexual affair with a man was at Provincetown, Massachusetts with a dancer named Kip Kiernan. He carried a photo of Kip in his wallet for many years. Having struggled with his sexuality throughout his youth, he came out as a gay man in private. When Kip left him for a woman and marriage, Williams was devastated. Williams was outed as gay by Louis Kronenberger in Time magazine in the 1950s.

After the success of The Glass Menagerie, Thomas Lanier Williams, later known as Tennessee, spent time in Mexico in late 1945. "I feel I was born in Mexico in another life," he wrote in a letter from Mexico City. Over the years, other writers—from Katherine Anne Porter to Williams' mentor, Hart Crane— had expressed the same sentiment. But luck was with Williams as he crossed la frontera at Piedras Negras/Eagle Pass: He met Pancho Rodriguez, a young Mexican American. The tale of that meeting would later be embellished—with Williams' car breaking down and a border guard's son helping to rescue a manuscript that border guards had confiscated. The rising 34-year-old playwright was immediately smitten with the 24-year-old Pancho—the border guard's son—and invited him to New Orleans as his live-in muse. The rest, as they say, is history. But the chronicle of their relationship was forgotten and, to a large extent, whitewashed from Williams' life story.

After the success of The Glass Menagerie, Thomas Lanier Williams, later known as Tennessee, spent time in Mexico in late 1945. "I feel I was born in Mexico in another life," he wrote in a letter from Mexico City. Over the years, other writers—from Katherine Anne Porter to Williams' mentor, Hart Crane— had expressed the same sentiment. But luck was with Williams as he crossed la frontera at Piedras Negras/Eagle Pass: He met Pancho Rodriguez, a young Mexican American. The tale of that meeting would later be embellished—with Williams' car breaking down and a border guard's son helping to rescue a manuscript that border guards had confiscated. The rising 34-year-old playwright was immediately smitten with the 24-year-old Pancho—the border guard's son—and invited him to New Orleans as his live-in muse. The rest, as they say, is history. But the chronicle of their relationship was forgotten and, to a large extent, whitewashed from Williams' life story.  His physical and emotional relationship with his secretary, Frank Merlo, lasted from 1947 until Merlo's death from cancer in 1961, and provided the stability during which Williams produced his most enduring works. Merlo was a balance to many of Williams's depressions, especially the fear that like his sister, Rose, he would become insane. The death of his lover drove Williams into a deep decade-long depression.

His physical and emotional relationship with his secretary, Frank Merlo, lasted from 1947 until Merlo's death from cancer in 1961, and provided the stability during which Williams produced his most enduring works. Merlo was a balance to many of Williams's depressions, especially the fear that like his sister, Rose, he would become insane. The death of his lover drove Williams into a deep decade-long depression. Conflicted over his own sexuality, Tennessee Williams wrote directly about homosexuality only in his short stories, his poetry, and his late plays. Williams's gayness was an open secret he neither publicly confirmed nor denied until the post-Stonewall era when gay critics took him to task for not coming out, which he did in a series of public utterances, his Memoirs (1975), self-portraits in some of the later plays, and the novel, Moise and the World of Reason (1975), all of which document, often pathetically, Williams's sense of himself as a gay man.

There are several volumes of witty, confessional letters to friends Donald Windham and Maria St. Just and a raft of cynical, exploitative kiss-and-tell books by men who claimed to know Williams well in his later, declining years. However, anyone who had read his stories and poems, in which Williams could be more candid than he could be in works written for a Broadway audience, had ample evidence of his homosexuality.

There are several volumes of witty, confessional letters to friends Donald Windham and Maria St. Just and a raft of cynical, exploitative kiss-and-tell books by men who claimed to know Williams well in his later, declining years. However, anyone who had read his stories and poems, in which Williams could be more candid than he could be in works written for a Broadway audience, had ample evidence of his homosexuality. Tennessee Williams's work poses fascinating problems for the gay reader. At his best, Williams wrote some of the greatest American plays, but though homosexuals are sometimes mentioned, they are dead, closeted safely in the exposition but never appearing on stage. In his post-Stonewall plays, in which openly homosexual characters appear, they serve only to dramatize Williams's negative feelings about his own homosexuality. In the 1940s and 1950s, Williams presented in his finest stories poetic renderings of homosexual desire, but homoeroticism was always linked to death. Only in his lyric poetry does one find positive expression of homoerotic desire.

These contradictions are not presented to damn Williams for not having a contemporary gay sensibility but to say that his attitude toward his own homosexuality reflected the era in which he lived. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, the McCarthy era, during which Williams wrote his best work, homosexuality branded one a traitor as well as a "degenerate."

These contradictions are not presented to damn Williams for not having a contemporary gay sensibility but to say that his attitude toward his own homosexuality reflected the era in which he lived. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, the McCarthy era, during which Williams wrote his best work, homosexuality branded one a traitor as well as a "degenerate." Williams's best work was an expression of his homosexuality combined with the intense neuroses that fueled his imagination and crippled his life. Gay critics have debated in recent years whether Williams's work is marked by "internalized homophobia" (Clum) or whether he is a subversive artist whose work can be best interpreted through the lens of leftist French theorists like Roland Barthes and Michel Foucault (Savran).

David Bergman sees Williams's characteristic linking of homosexuality and cannibalism as both religious (the homosexual as martyr) and Freudian (homosexuality as accommodation to and rebellion against the father figure), as well as part of a central American gay literary tradition that has its roots in the work of Herman Melville.

The diverse but complementary work of these critics can be read as necessary counters to the hete

rosexist critics of the past who either ignored Williams's homosexuality altogether or saw it as the root of his personal and artistic failings.

rosexist critics of the past who either ignored Williams's homosexuality altogether or saw it as the root of his personal and artistic failings. Williams died on February 25, 1983 at the age of 71. Reports at the time indicated he choked on an eyedrop bottle cap in his room at the Hotel Elysee in New York. The reports said he would routinely place the cap in his mouth, lean back, and place his eyedrops in each eye. The police report, however, suggested his use of drugs and alcohol contributed to his death. Prescription drugs, including barbiturates, were found in the room, and Williams' gag response may have been diminished by the effects of drugs and alcohol.

Suggested Further Readings:

- Barrios, Gregg. “The Kindness of Strangers” http://www.texasobserver.org/archives/item/14726-2124-afterword-the-kindness-of-strangershttp://www.texasobserver.org/archives/item/14726-2124-afterword-the-kindness-of-strangers

- Gussow, Mel. “Tennessee Williams on Art and Sex” http://www.nytimes.com/books/00/12/31/specials/williams-art.html

- “Happy Birthday, Tennessee Williams” http://www.washingtonblade.com/2011/03/24/happy-birthday-tennessee-williams/

- “New York City: Tennessee Williams’ Green Eyes – Up Close.” http://thenewgay.net/2011/01/tennessee-williams-green-eyes-up-close.html

- Paller, Michael. Gentlemen Callers: Tennessee Williams, Homosexuality, and Mid-Twentieth-Century Drama. (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005).

- “Tennessee Williams” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tennessee_Williams

- “Tennessee Williams” http://www.filmbug.com/db/344599

- “Williams, Tennessee (1911-1983)” http://www.glbtq.com/literature/williams_t.html

- Williams, Tennessee. Memoirs. (New York:New Directions, 2006).

- Williams, Tennessee. Notebooks. (New Haven, CT:Yale University Press, 2007).

Here's a rare find. Original PAJAMA (Paul Cadmus, Jared French, Margaret French) vintage gelatin silver print by Jared French (1905-1987) from the collection of Paul Cadmus.

A rare image of a nude Tennessee Williams (lower right) and Donald Windham to (upper left) dated 1943.

2 comments:

This is always a highlight of my day: reading your blog. Tennessee Williams has always been one of my favorite playwrights, and his work is awesome.

It's interesting that in high school and college, when I read and worked his plays, his life was never mentioned. We'd "analyze" his works, but I guess learning that he was gay was a taboo back in the 70's and 80's.

Thanks, as always, for a great piece.

Peace <3

Jay

Jay: I don't know where I first learned that Tennessee Williams was gay. I did attend a lecture about him when I was in high school, and though they discussed many aspects of his personal life and how it affected his plays, I can't remember if they mentioned that he was gay or not. I've always been a huge admirer of his work.

Post a Comment