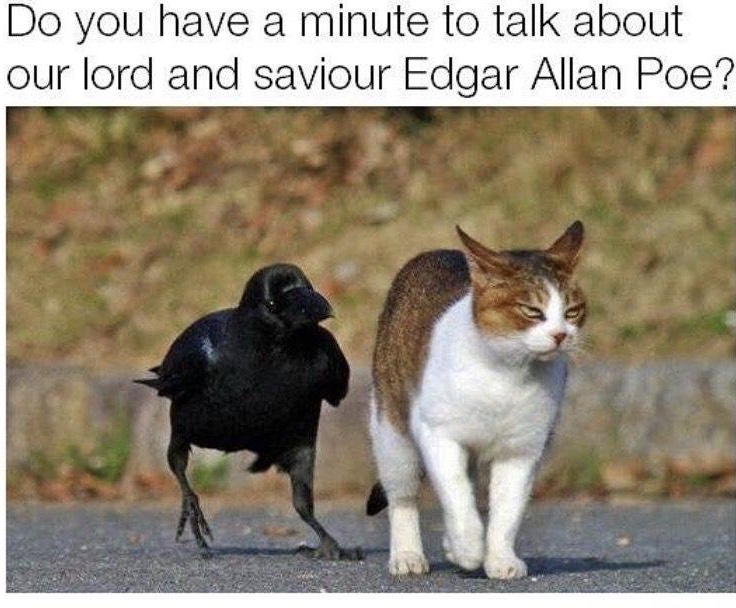

The Raven

By Edgar Allan Poe - 1809-1849

Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary,

Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore—

While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping,

As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door—

"'Tis some visitor," I muttered, "tapping at my chamber door—

Only this and nothing more."

Ah, distinctly I remember it was in the bleak December;

And each separate dying ember wrought its ghost upon the floor.

Eagerly I wished the morrow;—vainly I had sought to borrow

From my books surcease of sorrow—sorrow for the lost Lenore—

For the rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name Lenore—

Nameless here for evermore.

And the silken, sad, uncertain rustling of each purple curtain

Thrilled me—filled me with fantastic terrors never felt before;

So that now, to still the beating of my heart, I stood repeating,

"'Tis some visitor entreating entrance at my chamber door—

Some late visitor entreating entrance at my chamber door;—

This it is and nothing more."

Presently my soul grew stronger; hesitating then no longer,

"Sir," said I, "or Madam, truly your forgiveness I implore;

But the fact is I was napping, and so gently you came rapping,

And so faintly you came tapping, tapping at my chamber door,

That I scarce was sure I heard you"—here I opened wide the door;—

Darkness there and nothing more.

Deep into that darkness peering, long I stood there wondering, fearing,

Doubting, dreaming dreams no mortal ever dared to dream before;

But the silence was unbroken, and the stillness gave no token,

And the only word there spoken was the whispered word, "Lenore?"

This I whispered, and an echo murmured back the word, "Lenore!"—

Merely this and nothing more.

Back into the chamber turning, all my soul within me burning,

Soon again I heard a tapping somewhat louder than before.

"Surely," said I, "surely that is something at my window lattice;

Let me see, then, what thereat is, and this mystery explore—

Let my heart be still a moment and this mystery explore;—

'Tis the wind and nothing more!"

Open here I flung the shutter, when, with many a flirt and flutter,

In there stepped a stately Raven of the saintly days of yore;

Not the least obeisance made he; not a minute stopped or stayed he;

But, with mien of lord or lady, perched above my chamber door—

Perched upon a bust of Pallas just above my chamber door—

Perched, and sat, and nothing more.

Then this ebony bird beguiling my sad fancy into smiling,

By the grave and stern decorum of the countenance it wore,

"Though thy crest be shorn and shaven, thou," I said, "art sure no craven,

Ghastly grim and ancient Raven wandering from the Nightly shore—

Tell me what thy lordly name is on the Night's Plutonian shore!"

Quoth the Raven "Nevermore."

Much I marvelled this ungainly fowl to hear discourse so plainly,

Though its answer little meaning—little relevancy bore;

For we cannot help agreeing that no living human being

Ever yet was blest with seeing bird above his chamber door—

Bird or beast upon the sculptured bust above his chamber door,

With such name as "Nevermore."

But the Raven, sitting lonely on the placid bust, spoke only

That one word, as if his soul in that one word he did outpour.

Nothing further then he uttered—not a feather then he fluttered—

Till I scarcely more than muttered "Other friends have flown before—

On the morrow he will leave me, as my hopes have flown before."

Then the bird said "Nevermore."

Startled at the stillness broken by reply so aptly spoken,

"Doubtless," said I, "what it utters is its only stock and store

Caught from some unhappy master whom unmerciful Disaster

Followed fast and followed faster till his songs one burden bore—

Till the dirges of his Hope that melancholy burden bore

Of 'Never—nevermore.'"

But the Raven still beguiling my sad fancy into smiling,

Straight I wheeled a cushioned seat in front of bird, and bust and door;

Then, upon the velvet sinking, I betook myself to linking

Fancy unto fancy, thinking what this ominous bird of yore—

What this grim, ungainly, ghastly, gaunt and ominous bird of yore

Meant in croaking "Nevermore."

This I sat engaged in guessing, but no syllable expressing

To the fowl whose fiery eyes now burned into my bosom's core;

This and more I sat divining, with my head at ease reclining

On the cushion's velvet lining that the lamp-light gloated o'er,

But whose velvet violet lining with the lamp-light gloating o'er,

She shall press, ah, nevermore!

Then, methought, the air grew denser, perfumed from an unseen censer

Swung by Seraphim whose foot-falls tinkled on the tufted floor.

"Wretch," I cried, "thy God hath lent thee—by these angels he hath sent thee

Respite—respite and nepenthe, from thy memories of Lenore;

Quaff, oh quaff this kind nepenthe and forget this lost Lenore!"

Quoth the Raven "Nevermore."

"Prophet!" said I, "thing of evil!—prophet still, if bird or devil!—

Whether Tempter sent, or whether tempest tossed thee here ashore,

Desolate yet all undaunted, on this desert land enchanted—

On this home by Horror haunted—tell me truly, I implore—

Is there—is there balm in Gilead?—tell me—tell me, I implore!"

Quoth the Raven "Nevermore."

"Prophet!" said I, "thing of evil—prophet still, if bird or devil!

By that Heaven that bends above us—by that God we both adore—

Tell this soul with sorrow laden if, within the distant Aidenn,

It shall clasp a sainted maiden whom the angels name Lenore—

Clasp a rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name Lenore."

Quoth the Raven "Nevermore."

"Be that word our sign in parting, bird or fiend!" I shrieked, upstarting—

"Get thee back into the tempest and the Night's Plutonian shore!

Leave no black plume as a token of that lie thy soul hath spoken!

Leave my loneliness unbroken!—quit the bust above my door!

Take thy beak from out my heart, and take thy form from off my door!"

Quoth the Raven "Nevermore."

And the Raven, never flitting, still is sitting, still is sitting

On the pallid bust of Pallas just above my chamber door;

And his eyes have all the seeming of a demon's that is dreaming,

And the lamp-light o'er him streaming throws his shadow on the floor;

And my soul from out that shadow that lies floating on the floor

Shall be lifted—nevermore!

About the Poem

Just as it’s hard to post a poem about autumn without using a Robert Frost poem, it’s hard to post a poem for Halloween without a poem by Edgar Allan Poe. Whenever I read “The Raven,” I almost always hear it in the voice of Vincent Price. Is there anyone more perfect to read a Poe poem? Listen to it for yourself:

You can also hear classic readings of Poe’s “The Raven” by James Earl Jones, Christopher Walken, Neil Gaiman, Stan Lee, or John Astin.

"The Raven" is a narrative poem by American writer Edgar Allan Poe. First published in January 1845, the poem is often noted for its musicality, stylized language, and supernatural atmosphere. It tells of a talking raven's mysterious visit to a distraught lover, tracing the man's slow descent into madness. The lover, often identified as a student, is lamenting the loss of his love, Lenore. Sitting on a bust of Pallas, the raven seems to further distress the protagonist with its constant repetition of the word "Nevermore." The poem makes use of folk, mythological, religious, and classical references.

Poe claimed to have written the poem logically and methodically, intending to create a poem that would appeal to both critical and popular tastes, as he explained in his 1846 follow-up essay, "The Philosophy of Composition". The poem was inspired in part by a talking raven in the novel Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of Eighty by Charles Dickens. Poe based the complex rhythm and meter on Elizabeth Barrett's poem "Lady Geraldine's Courtship", and makes use of internal rhyme as well as alliteration throughout.

"The Raven" was first attributed to Poe in print in the New York Evening Mirror on January 29, 1845. Its publication made Poe popular in his lifetime, although it did not bring him much financial success. The poem was soon reprinted, parodied, and illustrated. Critical opinion is divided as to the poem's literary status, but it nevertheless remains one of the most famous poems ever written.

About the Poet

Like his life's work, Edgar Allan Poe's death remains shrouded in mystery. It was raining in Baltimore on October 3, 1849, but that didn't stop Joseph W. Walker, a compositor for the Baltimore Sun, from heading out to Gunner's Hall, a public house bustling with activity. It was Election Day, and Gunner's Hall served as a pop-up polling location for the 4th Ward polls. When Walker arrived at Gunner's Hall, he found a man, delirious and dressed in shabby second-hand clothes, lying in the gutter. The man was semi-conscious, and unable to move, but as Walker approached the him, he discovered something unexpected: the man was Edgar Allan Poe. Worried about the health of the addled poet, Walker stopped and asked Poe if he had any acquaintances in Baltimore that might be able to help him. Poe gave Walker the name of Joseph E. Snodgrass, a magazine editor with some medical training. Immediately, Walker penned Snodgrass a letter asking for help:

Baltimore City, Oct. 3, 1849

Dear Sir,

There is a gentleman, rather the worse for wear, at Ryan's 4th ward polls, who goes under the cognomen of Edgar A. Poe, and who appears in great distress, & he says he is acquainted with you, he is in need of immediate assistance.

Yours, in haste,

JOS. W. WALKER

To Dr. J.E. Snodgrass.

On September 27—almost a week earlier—Poe had left Richmond, Virginia, bound for Philadelphia to edit a collection of poems for Mrs. St. Leon Loud, a minor figure in American poetry at the time. When Walker found Poe in delirious disarray outside of the polling place, it was the first anyone had heard or seen of the poet since his departure from Richmond. Poe never made it to Philadelphia to attend to his editing business. Nor did he ever make it back to New York, where he had been living, to escort his aunt back to Richmond for his impending wedding. Poe was never to leave Baltimore, where he launched his career in the early 19th- century, again—and in the four days between Walker finding Poe outside the public house and Poe's death on October 7, he never regained enough consciousness to explain how he had come to be found, in soiled clothes not his own, incoherent on the streets. Instead, Poe spent his final days wavering between fits of delirium, gripped by visual hallucinations. The night before his death, according to his attending physician Dr. John J. Moran, Poe repeatedly called out for "Reynolds"—a figure who, to this day, remains a mystery.

Poe's death—shrouded in mystery—seems ripped directly from the pages of one of his own works. He had spent years crafting a careful image of a man inspired by adventure and fascinated with enigmas—a poet, a detective, an author, a world traveler who fought in the Greek War of Independence and was held prisoner in Russia. But though his death certificate listed the cause of death as phrenitis, or swelling of the brain, the mysterious circumstances surrounding his death have led many to speculate about the true cause of Poe's demise. "Maybe it’s fitting that since he invented the detective story," says Chris Semtner, curator of the Poe Museum in Richmond, Virginia, "he left us with a real-life mystery."

In 1867, one of the first theories to deviate from either phrenitis or alcohol was published by biographer E. Oakes Smith in her article "Autobiographic Notes: Edgar Allan Poe." "At the instigation of a woman, " Smith writes, "who considered herself injured by him, he was cruelly beaten, blow upon blow, by a ruffian who knew of no better mode of avenging supposed injuries. It is well known that a brain fever followed. . . ." Other accounts also mention "ruffians" who had beaten Poe senseless before his death. As Eugene Didier wrote in his 1872 article, "The Grave of Poe," that while in Baltimore, Poe ran into some friends from West Point, who prevailed upon him to join them for drinks. Poe, unable to handle liquor, became madly drunk after a single glass of champagne, after which he left his friends to wander the streets. In his drunken state, he "was robbed and beaten by ruffians, and left insensible in the street all night."

Others believe that Poe fell victim to a practice known as cooping, a method of voter fraud practiced by gangs in the 19th century where an unsuspecting victim would be kidnapped, disguised and forced to vote for a specific candidate multiple times under multiple disguised identities. Voter fraud was extremely common in Baltimore around the mid 1800s, and the polling site where Walker found the disheveled Poe was a known place that coopers brought their victims. The fact that Poe was found delirious on election day, then, is no coincidence.

Over the years, the cooping theory has come to be one of the more widely accepted explanations for Poe's strange demeanor before his death. Before Prohibition, voters were given alcohol after voting as a sort of reward; had Poe been forced to vote multiple times in a cooping scheme, that might explain his semi-conscious, ragged state.

Around the late 1870s, Poe's biographer J.H. Ingram received several letters that blamed Poe's death on a cooping scheme. A letter from William Hand Browne, a member of the faculty at Johns Hopkins, explains that "the general belief here is, that Poe was seized by one of these gangs, (his death happening just at election-time; an election for sheriff took place on Oct. 4th), 'cooped,' stupefied with liquor, dragged out and voted, and then turned adrift to die."

"A lot of the ideas that have come up over the years have centered around the fact that Poe couldn’t handle alcohol," says Semtner. "It has been documented that after a glass of wine he was staggering drunk. His sister had the same problem; it seems to be something hereditary."

Months before his death, Poe became a vocal member of the temperance movement, eschewing alcohol, which he'd struggled with all his life. Biographer Susan Archer Talley Weiss recalls, in her biography "The Last Days of Edgar A. Poe," an event, toward the end of Poe's time in Richmond, that might be relevant to theorists that prefer a "death by drinking" demise for Poe. Poe had fallen ill in Richmond, and after making a somewhat miraculous recovery, was told by his attending physician that "another such attack would prove fatal." According to Weiss, Poe replied that "if people would not tempt him, he would not fall," suggesting that the first illness was brought on by a bout of drinking.

Those around Poe during his finals days seem convinced that the author did, indeed, fall into that temptation, drinking himself to death. As his close friend J. P. Kennedy wrote on October 10, 1849: "On Tuesday last Edgar A. Poe died in town here at the hospital from the effects of a debauch. . . . He fell in with some companion here who seduced him to the bottle, which it was said he had renounced some time ago. The consequence was fever, delirium, and madness, and in a few days a termination of his sad career in the hospital. Poor Poe! . . . A bright but unsteady light has been awfully quenched."

Though the theory that Poe's drinking lead to his death fails to explain his five-day disappearance, or his second-hand clothes on October 3, it was nonetheless a popular theory propagated by Snodgrass after Poe's death. Snodgrass, a member of the temperance movement, gave lectures across the country, blaming Poe's death on binge drinking. Modern science, however, has thrown a wrench into Snodgrasses talking points: samples of Poe's hair from after his death show low levels of lead, explains Semtner, which is an indication that Poe remained faithful to his vow of sobriety up until his demise.

In 1999, public health researcher Albert Donnay argued that Poe's death was a result of carbon monoxide poisoning from coal gas that was used for indoor lighting during the 19th century. Donnay took clippings of Poe's hair and tested them for certain heavy metals that would be able to reveal the presence of coal gas. The test was inconclusive, leading biographers and historians to largely discredit Donnay's theory.

While Donnay's test didn't reveal levels of heavy metal consistent with carbon monoxide poisoning, the tests did reveal elevated levels of mercury in Poe's system months before his death. According to Semtner, Poe's mercury levels were most likely elevated as a result of a cholera epidemic he'd been exposed to in July of 1849, while in Philadelphia. Poe's doctor prescribed calomel, or mercury chloride. Mercury poisoning, Semtner says, could help explain some of Poe's hallucinations and delirium before his death. However, the levels of mercury found in Poe's hair, even at their highest, are still 30 times below the level consistent with mercury poisoning.

In 1996, Dr. R. Michael Benitez was participating in a clinical pathologic conference where doctors are given patients, along with a list of symptoms, and instructed to diagnose and compare with other doctors as well as the written record. The symptoms of the anonymous patient E.P., "a writer from Richmond" were clear: E.P. had succumbed to rabies. According to E.P.'s supervising physician, Dr. J.J. Moran, E.P. had been admitted to a hospital due to "lethargy and confusion." Once admitted, E.P.'s condition began a rapid downward spiral: shortly, the patient was exhibiting delirium, visual hallucinations, wide variations in pulse rate and rapid, shallow breathing. Within four days—the median length of survival after the onset of serious rabies symptoms—E.P. was dead.

E.P., Benitez soon found out, wasn't just any author from Richmond. It was Poe whose death the Maryland cardiologist had diagnosed as a clear case of rabies, a fairly common virus in the 19th century. Running counter to any prevailing theories at the time, Benitez's diagnosis ran in the September 1996 issue of the Maryland Medical Journal. As Benitez pointed out in his article, without DNA evidence, it's impossible to say with 100 percent certainty that Poe succumbed to the rabies virus. There are a few kinks in the theory, including no evidence of hydrophobia (those afflicted with rabies develop a fear of water, Poe was reported to have been drinking water at the hospital until his death) nor any evidence of an animal bite (though some with rabies don't remember being bitten by an animal). Still, at the time of the article's publication, Jeff Jerome, curator of the Poe House Museum in Baltimore, agreed with Benitez's diagnosis. "This is the first time since Poe died that a medical person looked at Poe's death without any preconceived notions," Jerome told the Chicago Tribune in October of 1996. "If he knew it was Edgar Allan Poe, he'd think, 'Oh yeah, drugs, alcohol,' and that would influence his decision. Dr. Benitez had no agenda."

One of the most recent theories about Poe's death suggests that the author succumbed to a brain tumor, which influenced his behavior before his death. When Poe died, he was buried, rather unceremoniously, in an unmarked grave in a Baltimore graveyard. Twenty-six years later, a statue was erected, honoring Poe, near the graveyard's entrance. Poe's coffin was dug up, and his remains exhumed, in order to be moved to the new place of honor. But more than two decades of buried decay had not been kind to Poe's coffin—or the corpse within it—and the apparatus fell apart as workers tried to move it from one part of the graveyard to another. Little remained of Poe's body, but one worker did remark on a strange feature of Poe's skull: a mass rolling around inside. Newspapers of the day claimed that the clump was Poe's brain, shriveled yet intact after almost three decades in the ground.

We know, today, that the mass could not be Poe's brain, which is one of the first parts of the body to rot after death. But Matthew Pearl, an American author who wrote a novel about Poe's death, was nonetheless intrigued by this clump. He contacted a forensic pathologist, who told him that while the clump couldn't be a brain, it could be a brain tumor, which can calcify after death into hard masses.

According to Semtner, Pearl isn't the only person to believe Poe suffered from a brain tumor: a New York physician once told Poe that he had a lesion on his brain that caused his adverse reactions to alcohol.

A far less sinister theory suggests that Poe merely succumbed to the flu—which might have turned into deadly pneumonia—on this deathbed. As Semtner explains, in the days leading up to Poe's departure from Richmond, the author visited a physician, complaining of illness. "His last night in town, he was very sick, and his [soon-to-be] wife noted that he had a weak pulse, a fever, and she didn’t think he should take the journey to Philadelphia," says Semtner. "He visited a doctor, and the doctor also told him not to travel, that he was too sick." According to newspaper reports from the time, it was raining in Baltimore when Poe was there—which Semtner thinks could explain why Poe was found in clothes not his own. "The cold and the rain exasperated the flu he already had," says Semtner, "and maybe that eventually lead to pneumonia. The high fever might account for his hallucinations and his confusion."

In his 2000 book Midnight Dreary: The Mysterious Death of Edgar Allan Poe, author John Evangelist Walsh presents yet another theory about Poe's death: that Poe was murdered by the brothers of his wealthy fiancée, Elmira Shelton. Using evidence from newspapers, letters and memoirs, Walsh argues that Poe actually made it to Philadelphia, where he was ambushed by Shelton's three brothers, who warned Poe against marrying their sister. Frightened by the experience, Poe disguised himself in new clothes (accounting for, in Walsh's mind, his second-hand clothing) and hid in Philadelphia for nearly a week, before heading back to Richmond to marry Shelton. Shelton's brothers intercepted Poe in Baltimore, Walsh postulates, beat him, and forced him to drink whiskey, which they knew would send Poe into a deathly sickness. Walsh's theory has gained little traction among Poe historians—or book reviewers; Edwin J. Barton, in a review for the journal American Literature, called Walsh's story "only plausible, not wholly persuasive." "Midnight Dreary is interesting and entertaining," he concluded, "but its value to literary scholars is limited and oblique."

---

For Semtner, however, none of the theories fully explain Poe's curious end. "I've never been completely convinced of any one theory, and I believe Poe's cause of death resulted from a combination of factors," he says. "His attending physician is our best source of evidence. If he recorded on the mortality schedule that Poe died of phrenitis, Poe was most likely suffering from encephalitis or meningitis, either of which might explain his symptoms."

HAPPY HALLOWEEN

1 comment:

I don't appreciate Halloween in my country ,I prefer

Laetare Sunday

Post a Comment