|

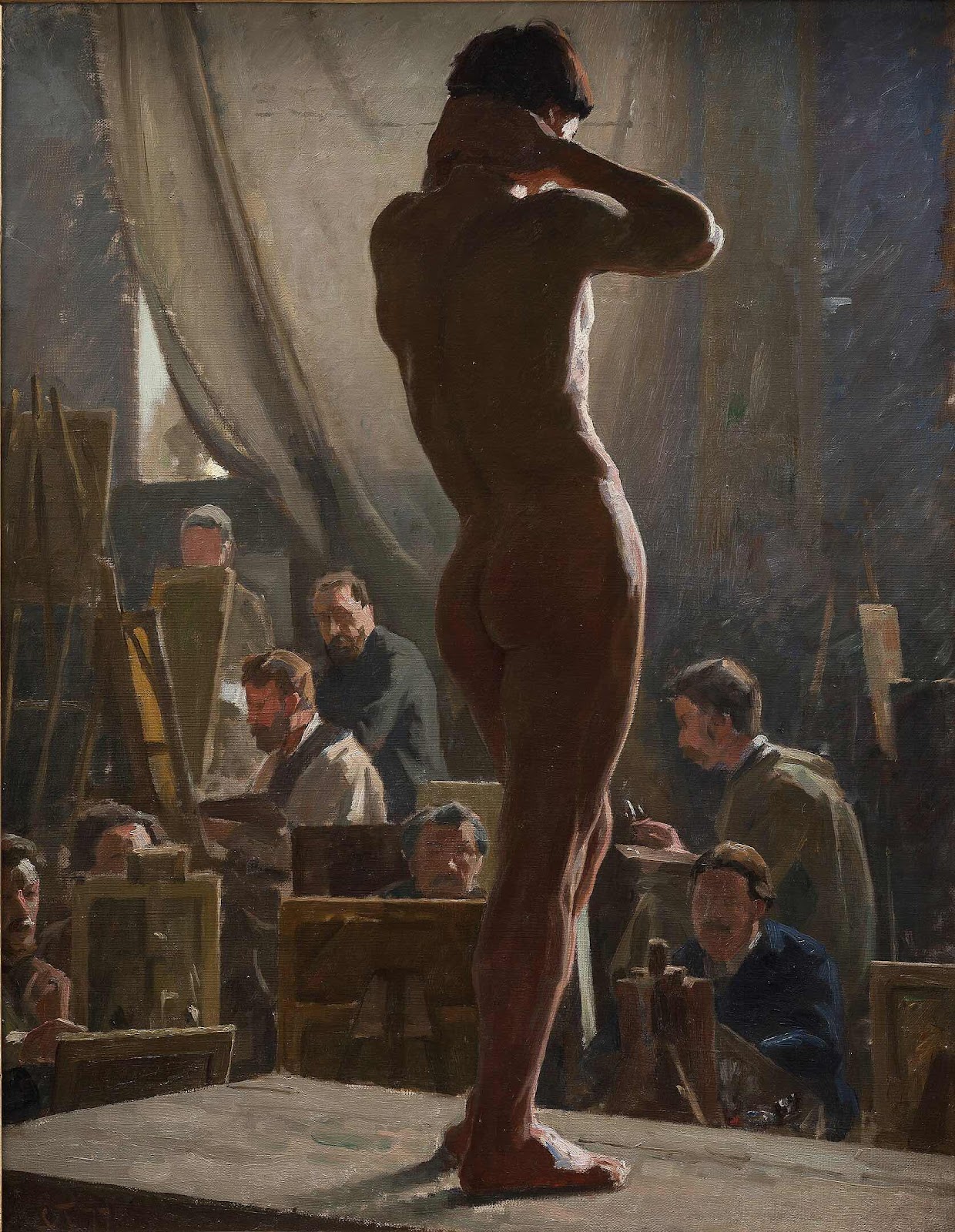

Male Nude in the Studio of Bonnat, Laurits Tuxen (1877) |

Long before museums and galleries became the homes of the male nude, it lived in the studios. In the ateliers of the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the Royal Academy in London, and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in the United States, generations of students learned the ideal proportions of the human form not through imagination—but by closely observing the naked man before them.

|

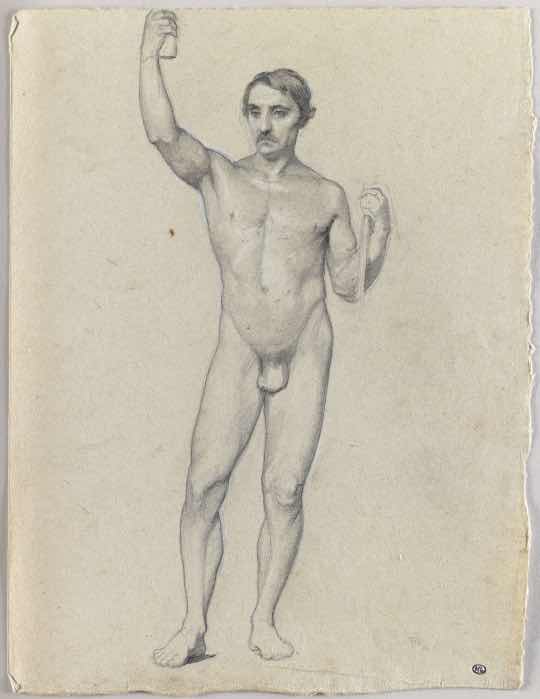

Paul Delaroche’s Study of a Male Nude (c. 1835) |

The academic nude wasn’t just a subject of study; it was a rite of passage. Drawing the male model became a disciplined practice that shaped not only artists’ technical skill, but also Western ideals of masculinity, beauty, and form. In the 19th century, the École des Beaux-Arts institutionalized the male nude as the pinnacle of artistic study. The male figure, more than the female, was thought to embody harmony and proportion, a living reference to both ancient sculpture and Renaissance anatomical studies. The famed “Concours de Torse,” or Torso Competition, showcased how aspiring painters honed their craft on the male body, rendering each muscle with academic precision. A striking example is Paul Delaroche’s

Study of a Male Nude (c. 1835), a dramatically lit figure standing in a contrapposto pose, his flesh rendered with the same reverence one might apply to a marble Apollo. Here, individuality fades; the model becomes a type, a vessel for timeless ideals.

|

Study of a Male Nude Seen from Behind, William Etty (c. 1830s) |

In London, the Royal Academy Schools upheld similar values. Students began by copying antique plaster casts, gradually earning the right to work in the Life Room, where a live male model stood nude on a platform under harsh light and stricter silence. These models often came from the working classes, their anonymity preserved even as their bodies were meticulously recorded in sketch after sketch. William Etty, a British painter committed to the nude in an often prudish art culture, created countless studies that quietly smuggled eroticism into the academic process. His

Study of a Male Nude Seen from Behind (c. 1830s), now housed at Tate Britain, transforms a backlit model into an object of lyrical sensuality, every curve of the body rendered with lingering attention.

|

Bill Duckett Nude, Thomas Eakins (ca. 1889) |

In the United States, Thomas Eakins redefined the academic nude—and ignited controversy. At the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Eakins encouraged both male and female students to observe fully nude male models, a practice that pushed the limits of American Victorian propriety. He sometimes posed nude himself, blurring the boundaries between instructor, artist, and subject. One of his oil sketches of which no photo exists,

The Male Nude (c. 1885), strips away allegory or idealism entirely. A model sits awkwardly, raw and unguarded. There is no attempt to mythologize or elevate, only to observe. The tension in Eakins’s work lies in this realism—an almost clinical intimacy that reveals more than anatomy.

|

Young Male Nude Seated by the Sea, Jean-Hippolyte Flandrin (1836) |

Though most academic studies of the nude remained in the studio, some evolved into finished works for public exhibition. These retained the formal lessons of the academy while cloaking the nude in mythological or historical justification. Jean-Hippolyte Flandrin’s Y

oung Male Nude Seated by the Sea (1836) exemplifies this genre. A solitary youth, nude and introspective, sits beside an imagined shore. The painting, while formally academic, gestures toward emotional vulnerability and latent desire. It is not just an ideal—it is a reverie. Often described as “the most beautiful boy in French painting,” the figure suggests a coded eroticism beneath its classical restraint.

|

A Life Class, Unidentified artist and Formerly attributed to William Hogarth (c. early 19th century) |

The art school nude was shaped not just by technique, but by a complex social structure. The model—often unnamed—was a laborer in a rarefied world. In the archives of the École des Beaux-Arts or the Musée Rodin, one finds charcoal drawings of men reclining, lunging, or simply standing, their bodies lit and studied as if they were statues. An anonymous drawing from around 1890 captures a reclining male nude in dramatic foreshortening—an image at once clinical and intimate. These men were employed for their endurance, strength, and presence. Though rarely memorialized, their bodies shaped generations of artists' understanding of the human form.

The academic nude may appear orderly or formulaic, but beneath its surface lies a subtle history of aesthetic pleasure, regulation, and coded longing. In the Life Room, artists were taught not only how to render the male body, but how to look at it—intently, repeatedly, and within the sanctioned space of artistic discipline. Today, those once-forgotten studies are being reconsidered—not just as technical exercises, but as visual records of how masculinity was taught, observed, and quietly desired.

No comments:

Post a Comment