Publius Aelius Hadrianus, commonly known as Hadrian, followed his uncle Trajan as emperor of Rome, ruling from 117-38 A.D. As emperor he was known for touring and consolidating the empire's far-flung frontiers. In Britain he ordered the construction of what is now known as Hadrian's Wall, near the modern border of England and Scotland. The wall, 73 miles long, five meters high and three meters wide, marked the northern edge of the Roman empire. He is considered one of the five good emperors, and probably the one who most openly homosexual (or possibly bisexual).

Publius Aelius Hadrianus, commonly known as Hadrian, followed his uncle Trajan as emperor of Rome, ruling from 117-38 A.D. As emperor he was known for touring and consolidating the empire's far-flung frontiers. In Britain he ordered the construction of what is now known as Hadrian's Wall, near the modern border of England and Scotland. The wall, 73 miles long, five meters high and three meters wide, marked the northern edge of the Roman empire. He is considered one of the five good emperors, and probably the one who most openly homosexual (or possibly bisexual). Hadrian's homosexual relationship with the Greek youth Antinous is well known through history and remains one of the defining parts of his reign.It is said that ,while the two were on a tour of Egypt, Antinous fell off of a barge in the Nile and died.The loss of his young lover made Hadrian go insane and he immediately deified the youth and had cults developed to worship him.Hadrian also named some cities throughout the empire after him.

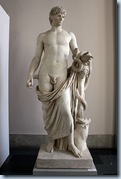

When it comes to Hadrian's apparent homosexuality, then the accounts remain vague and unclear. Most of the attention centers on the young Antinous, whom Hadrian grew very fond of. Statues of Antinous have survived, showing that imperial patronage of this youth extended to having sculptures made of him. In AD 130 Antinous accompanied Hadrian to Egypt. It was on a trip on the Nile when Antinous met with an early and somewhat mysterious death. Officially, he fell from the boat and drowned. But a persistent rumor spoke of Antinous having been a sacrifice in some bizarre eastern ritual.

The reasons for the young man's death might not be clear, but was is known is that Hadrian grieved deeply for Antinous. He even founded a city along the banks of the Nile where Antinous had drowned, Antinoopolis. Touching as this might have seemed to some, it was an act deemed unbefitting an emperor and drew much ridicule.

The year of Antinous’s death, 130, appears to mark the beginning of Hadrian’s decline. The young Greek had accompanied him during his most active, energetic and successful time, from their meeting in Bithynia in 124 on, when the latter was 13 or 14, through the heyday of their second stay in Athens in 128, up to his mysterious end in the Nile. Whether this was an accident, murder or suicide remains an unresolved question. The superstitious youth might have wanted to offer his life for Hadrian’s health, but also this is only a possible guess. At the place of the fatal event, Hadrian founded a town of Greek settlers, Antinoopolis. Its impressive ruins were still seen by European travelers in the early 19th century, but have completely disappeared since. It is not clear whether the remains of Antinous were buried there or near Rome, at a still existent obelisk which might have been only a cenotaph. The Antinous cult was not generally accepted in the Latin, western parts of the Empire, but in Egypt he was identified with Osiris; temples were built and games held in memory of him in several Greek towns too.

The year of Antinous’s death, 130, appears to mark the beginning of Hadrian’s decline. The young Greek had accompanied him during his most active, energetic and successful time, from their meeting in Bithynia in 124 on, when the latter was 13 or 14, through the heyday of their second stay in Athens in 128, up to his mysterious end in the Nile. Whether this was an accident, murder or suicide remains an unresolved question. The superstitious youth might have wanted to offer his life for Hadrian’s health, but also this is only a possible guess. At the place of the fatal event, Hadrian founded a town of Greek settlers, Antinoopolis. Its impressive ruins were still seen by European travelers in the early 19th century, but have completely disappeared since. It is not clear whether the remains of Antinous were buried there or near Rome, at a still existent obelisk which might have been only a cenotaph. The Antinous cult was not generally accepted in the Latin, western parts of the Empire, but in Egypt he was identified with Osiris; temples were built and games held in memory of him in several Greek towns too. Despite his increasing illness, Hadrian managed to rule efficiently also in his last years. In Rome he founded a kind of university, the Athenaeum. Nevertheless he was but a shadow of his former self, and had to think of a successor. Apparently his brother-in-law, Servianus, who was 90 years old but tenacious of life, hoped that he might be the Emperor’s heir. He was accused of conspiracy and executed together with his grandson. Afterwards Hadrian adopted Ceionus Commodus, whom he called Aelius Verus, and who was an easy-going and to all appearances not very promising man. Some loose tongues suggested that he owed his distinction to the favors he had once granted Hadrian, which could have hardly explained this preference, though. Instead it seems not completely unlikely that Verus was Hadrian’s son, but this also only surmise. However, Verus died of tuberculosis on New Year of 138, which was another blow to Hadrian. But his next choice turned out a better one, as he adopted Antoninus, then 51-year-old, a perfectly honest man, benign and even-tempered. He lacked Hadrian’s intellectual brilliancy and versatility, but also his restlessness and inconsistency. Antoninus Pius was to be Emperor for 23 years, during which he never left Italy. Hadrian had looked even farther forward and made Antoninus adopt his 16-year-old nephew, Marcus Annius Verus, who was to be the Emperor Marcus Aurelius, and also a Stoic philosopher famous for his ‘Meditations’. The ‘Antonine Age’ became a synonym for a time of peace and prosperity.

Despite his increasing illness, Hadrian managed to rule efficiently also in his last years. In Rome he founded a kind of university, the Athenaeum. Nevertheless he was but a shadow of his former self, and had to think of a successor. Apparently his brother-in-law, Servianus, who was 90 years old but tenacious of life, hoped that he might be the Emperor’s heir. He was accused of conspiracy and executed together with his grandson. Afterwards Hadrian adopted Ceionus Commodus, whom he called Aelius Verus, and who was an easy-going and to all appearances not very promising man. Some loose tongues suggested that he owed his distinction to the favors he had once granted Hadrian, which could have hardly explained this preference, though. Instead it seems not completely unlikely that Verus was Hadrian’s son, but this also only surmise. However, Verus died of tuberculosis on New Year of 138, which was another blow to Hadrian. But his next choice turned out a better one, as he adopted Antoninus, then 51-year-old, a perfectly honest man, benign and even-tempered. He lacked Hadrian’s intellectual brilliancy and versatility, but also his restlessness and inconsistency. Antoninus Pius was to be Emperor for 23 years, during which he never left Italy. Hadrian had looked even farther forward and made Antoninus adopt his 16-year-old nephew, Marcus Annius Verus, who was to be the Emperor Marcus Aurelius, and also a Stoic philosopher famous for his ‘Meditations’. The ‘Antonine Age’ became a synonym for a time of peace and prosperity. For the time being, it seemed that the curse called down by Servianus on his brother-in-law, that Hadrian should wish to die but not be able to, came true. He commanded a slave to kill him with a sword, who flew upset, and entreated a doctor to poison him, who committed suicide. Finally Hadrian tried to stab himself to death, but was overwhelmed by his guards. Then he lamented that he should have the power to kill others but not himself. The alarmed Antoninus admonished him to resign to his fate, because he, Antoninus, would not be better than a parricide if he should agree to the killing of Hadrian.

Meanwhile, the summer had begun and an oppressive heat made the stay in Tibur intolerable. Hadrian went to Baiae, a sea resort at the Gulf of Naples. Here he died on the 10th of July, 138, a few days after he had written these lines in Latin:

Animula vagula blandulaAnd for a final note of irony, the mausoleum built for Hadrian has been used by the Popes as a fortress for centuries to guard Vatican City. How is it that the grave of one of Rome’s most famous homosexuals, became the guardian of Catholicism? It didn’t help that when the Bubonic Plague hit Rome and the pope prayed for relief, an angel appeared atop the mausoleum and ended the plague.

hospes comesque corporis

quae nunc abibis in loca

pallidula rigida nudula

nec ut soles dabis iocos

(Vagrant soul, you tender one,

guest and fellow of the body,

Now you have to descend into places

pallid and rigid and nude,

Nor will you be playful as you used to be.)

The Mausoleum of Hadrian, usually known as the Castel Sant'Angelo, is a towering cylindrical building in Rome, initially commissioned by the Roman Emperor Hadrian as a mausoleum for himself and his family. The building was later used as a fortress and castle, and is now a museum. The tomb of the Roman emperor Hadrian, also called Hadrian's mole, was erected on the right bank of the Tiber, between 135 AD and 139 AD. Originally the mausoleum was a decorated cylinder, with a garden top and golden quadriga. Hadrian's ashes were placed here a year after his death in Baiae in 138 AD, together with those of his wife Sabina, and his first adopted son, Lucius Aelius, who also died in 138 AD. Following this, the remains of succeeding emperors were also placed here, the last recorded deposition being Caracalla in 217 AD. The urns containing these ashes were probably placed in what is now known as the Treasury room deep within the building.

No comments:

Post a Comment